In the last entry, I introduced you to 18th century botanist Carl Linnaeus, and described his major contribution to biology: a universal taxonomic system. Today, I want to take another look at taxonomy, and discuss some of the flaws in this now dated and obsolete classification system, some solutions to these problems, and what it means for the bigger picture of life on earth. So join me as we explore life, in endless forms beautiful.

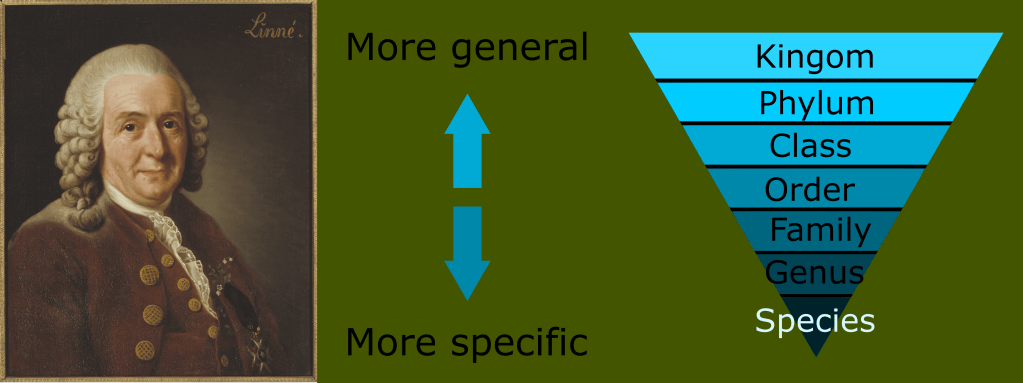

Carl Linneaus was a swedish botanist who is the author of one of the most versatile and universal systems of taxonomy. His greatest insight was noticing that all creatures fit into a larger pattern of nested fundamental similarities becoming more general the broader one looked, and more specific the narrower one’s focus.

He envisioned a hierarchical system of broadly similar groups gradually diverging into more specific and numerous divisions of organisms culminating with members of reproductively isolated breeding populations called species. This system of nested hierarchies inadvertently revealed the common ancestry of all life, and was an important contributing factor to the discovery of evolution.

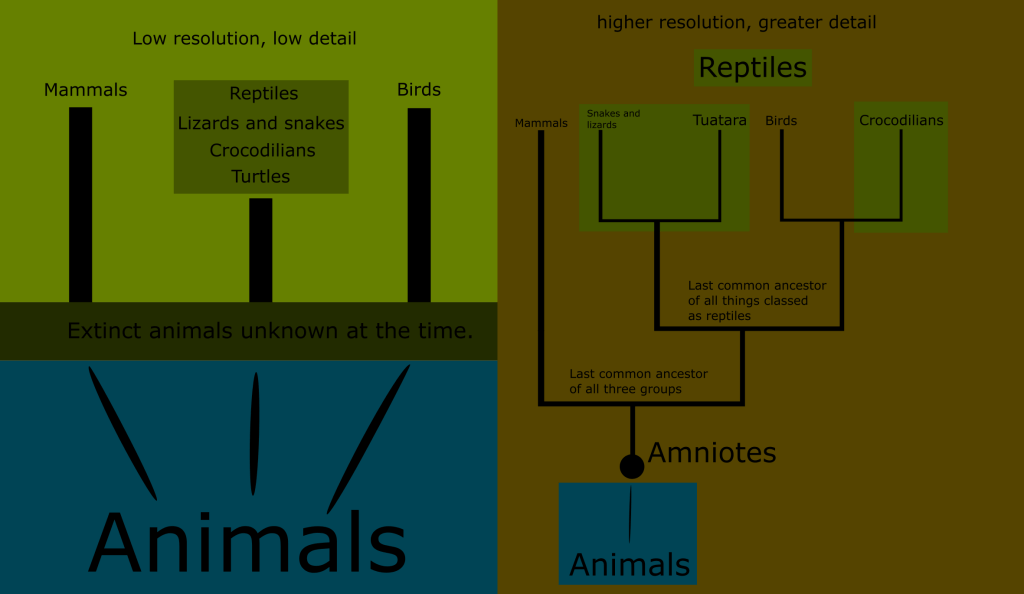

The linnaean system can be thought of as something like a low resolution snapshot of the history of life. It worked to group extant organisms into familiar categories, while providing some level of context into how they fit into the larger scheme of biological development.

But for all its strengths, the Linnaean taxonomic system does suffer from a handful of flaws that could not have been predicted in Linn’s day. For what he had to work with, it was remarkable for its time. But we now recognize that it is no longer sufficient to contain and describe the vast array of organisms known today. Let’s take a closer look at why.

First, the Linnaean system assumes equal ranks for all lineages of organisms. This is because the system does not take the ancestry of life into account, being conceived by creationists who had not yet realized how life develops.

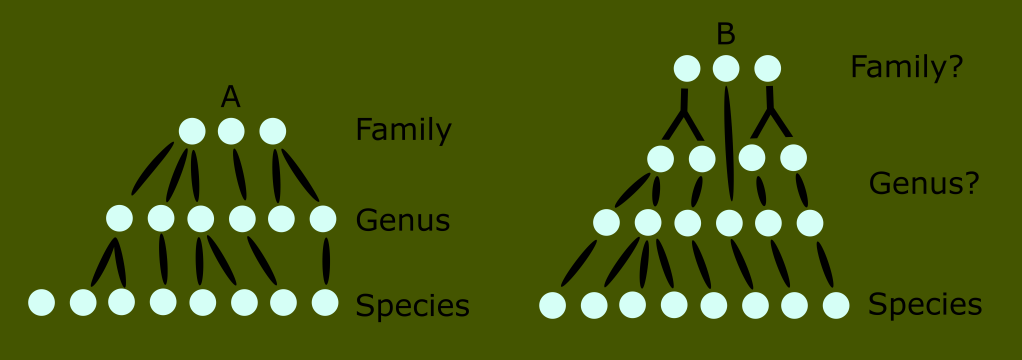

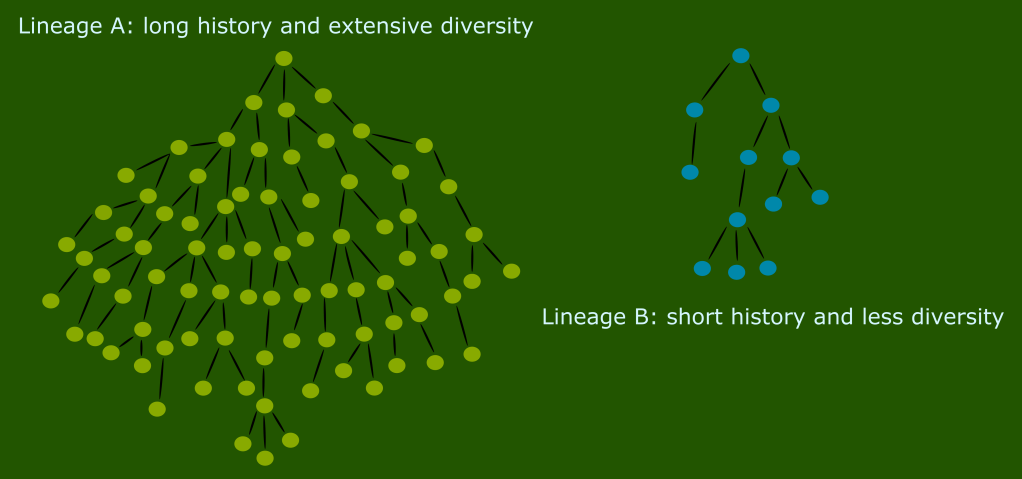

For example, let’s say we have two lineages of organisms to classify.

For the first, let’s call it lineage A, we assume a nice simple three level relationship at the bottom which we will call family, genus and species.

But let’s compare the same level of classification with an organism (B) that has greater diversity in its population.

We can see that developments within this group, represented by the circles with other groups diverging from them, meaning that there is more between the “genus” and “family” level for this group as opposed to the other one.

Are these extra divisions at the family level, or the genus level? The fact that we think to ask this question reveals the problem; because of our previously defined ranks, we assume it must be one or the other. Put another way, we intuit that life must somehow fit itself into our ranked system, rather than creating our system to take the branching and convoluted nature of life into account. It is important to note that these ranks are entirely arbitrary categories intended to provide a reference to make it easier to think about populations.

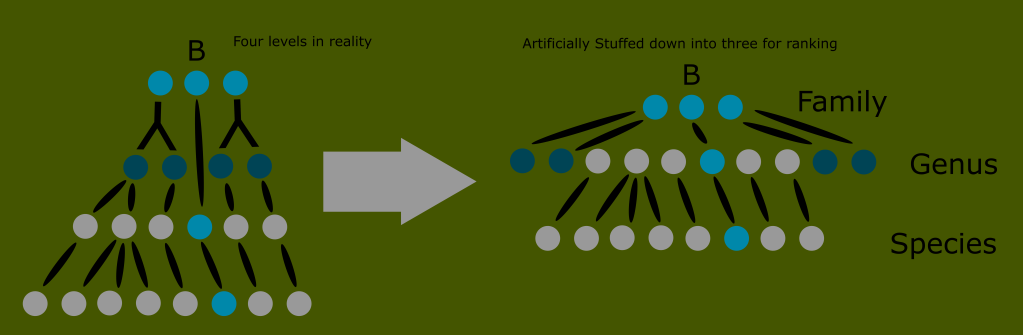

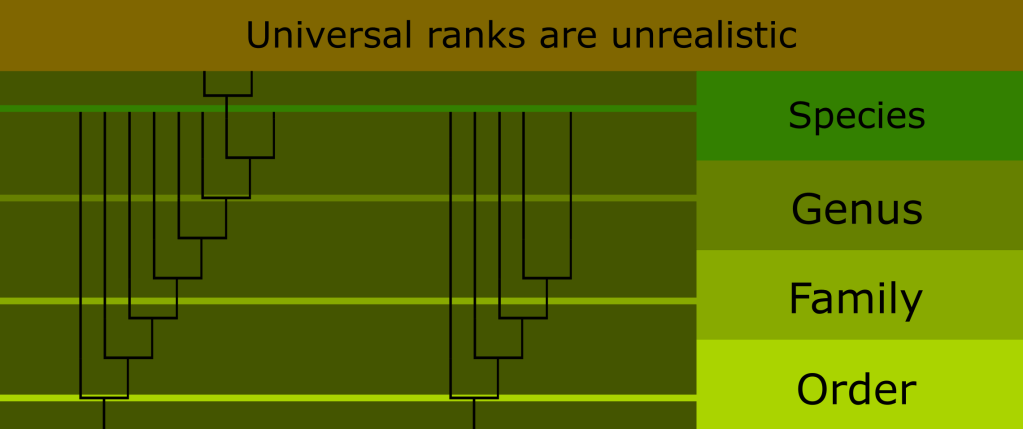

This visual illustrates where the Linnaean system breaks down when there is rapid speciation, large levels of diversity in a lineage, or a lineage that has existed for a long time relative to another, and will therefore have a longer family history.

Another problem this visual can illustrate is that it fails to accurately reflect evolutionary history. In this example, we have forced the varying developments into the classic ranks for the sake of consistency.

But how are we to know that the genera are not of equal rank? Nothing about this arrangement implies the relationship of the grey genera to the dark blue ones, the implication is that they are of equal rank, despite one being the ancestor of the other.

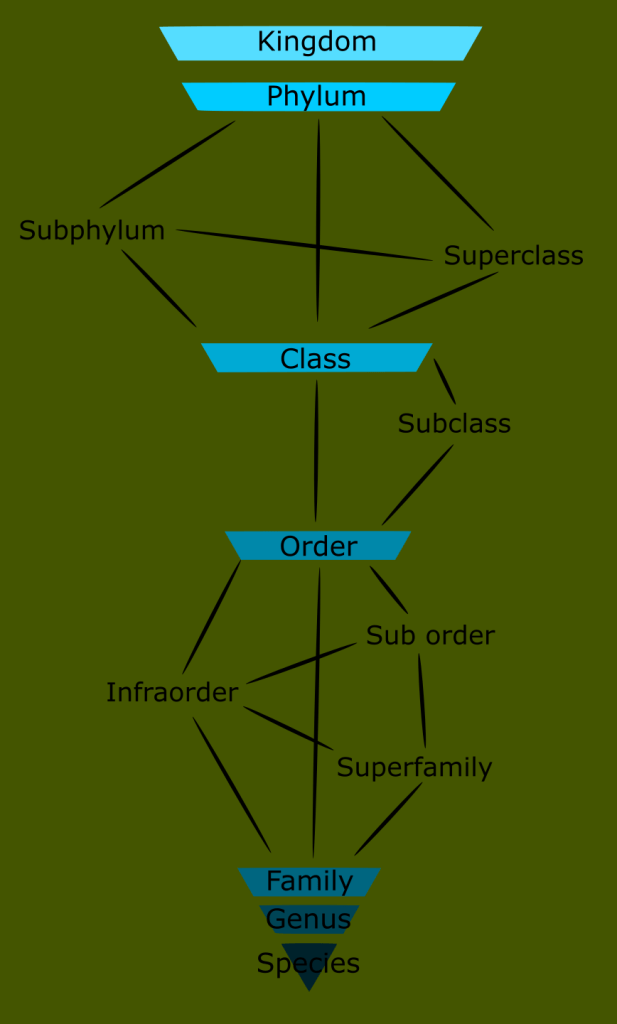

One way to solve this is by adding additional groups where needed. Since not all family trees are equal, this eventually causes the Linnaean system to break down into a confusing patchwork with some groups requiring auxiliary categorizations right next to taxons that don’t.

The problem is that now that we allow as many categories as we need, we quickly run out of Linnaean names. We can add a higher and lower category above and below each rank, but the few extra categories this affords us still does not come close to the number that exist in nature. These inter-ranks are applied inconsistently, due to the fact that different lineages are not symmetrical; thus we are forced to partially disassemble our neat system of equal ranks in order to accommodate varying degrees of relatedness, this renders the system too convoluted to be readily used.

For example, There are over 40,000 species of spiders, who first appeared in the fossil record dating back to just under around 400 million years ago. By contrast, there are 1500 species of rodents, making their first appearance a mere 54 million years ago. There are about 40 species of cats, appearing 35 million years ago.

Do you suppose their family trees will be equal in length, and number of branches, and diversity such that they can all be condensed into the same number of equal ranked groupings?

The fact that not all lineages are symmetrical means that the whole idea of predetermined, equal ranks is misguided from the beginning. When we account for all of these additional branches, nodes, forks and long histories, our neat categorical set becomes disconnected and stretched out into something that resembles more of a tree.

A ranked system to describe each member of a family tree for just a few generations of one family would break down with all of the outliers, exceptions and special circumstances that pile up. The more generations we include, the more the pattern of a convoluted tree emerges. This is the crux of it, the Linnaean system is envisioned as hierarchy of linear ranks, but it is attempting to describe a network of interrelated populations spanning the entire range of all life.

This situation is further complicated by the fact that different lineages also have varying degrees of differentiation as well. What this means is that while ancestral relationships are relatively straightforward for exclusively sexually reproductive organisms like animals, the web becomes even more tangled with plants. Many plants are able to hybridize between species, and produce viable offspring such that their lineages mix and match more easily and in more ways than animals.

The only way forward is to simply embrace the branching nature of family trees and take to heart that different lineages are not equivalent, and that the web of life is a lot more convoluted and complex than Linnaeus’ neat and tidy system could ever have accounted for. This means that the entire concept of an equally ranked system such as Linnaeus initially envisioned is not only impossible, it doesn’t make sense to even try.

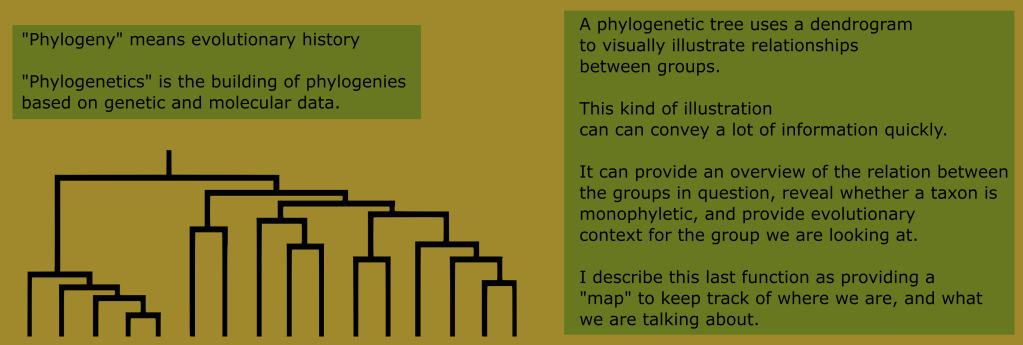

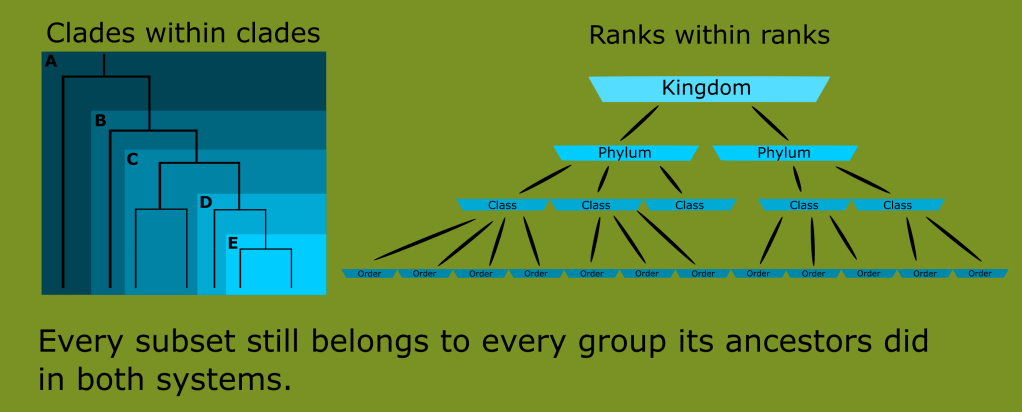

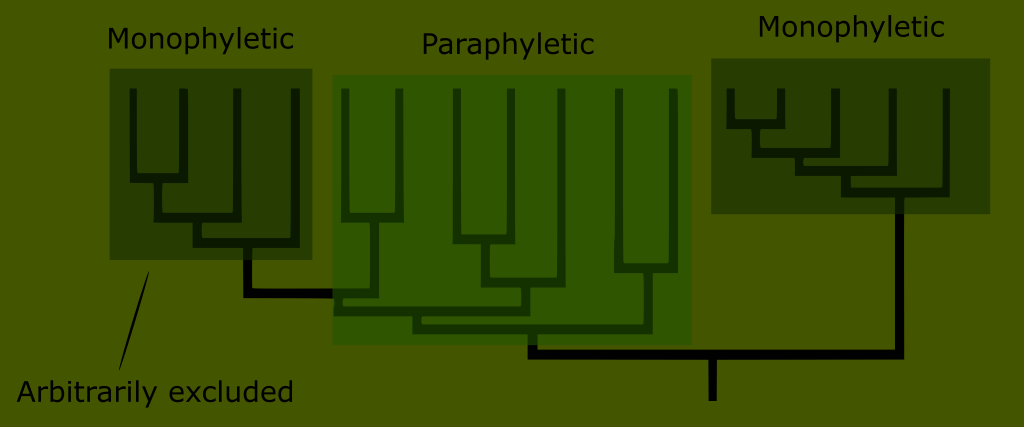

The new taxonomic system uses phylogenetic trees to classify and trace family histories. In this way as many categories as are needed can be made to reflect the evident ancestry. When we find a lineage of organisms that evidently arose from a common ancestor it forms a distinct branch. When this happens, we say that these organisms form a clade; a group that includes a common ancestor and all its descendants. Such a clade is monophyletic, because it includes all its descendants and thus represents a single grouping.

One benefit is that that these divisions are objectively real, as opposed to arbitrary ranks we can invent for the sake of naming things. We are able to ask, “do these organisms form a clade?” not “how can we classify them?”

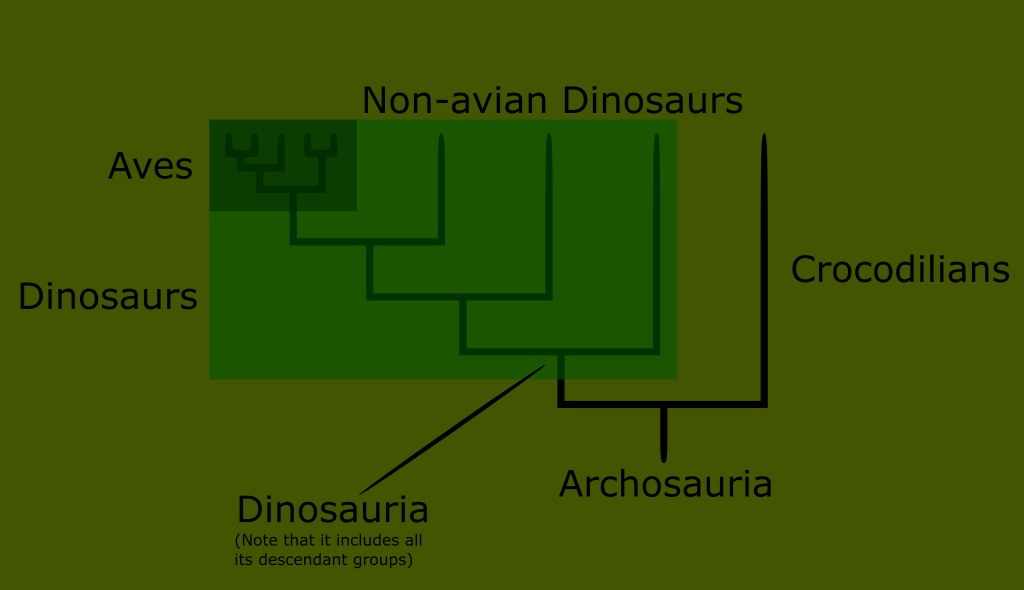

Here is an example of a monophyletic clade that is familiar to us today.

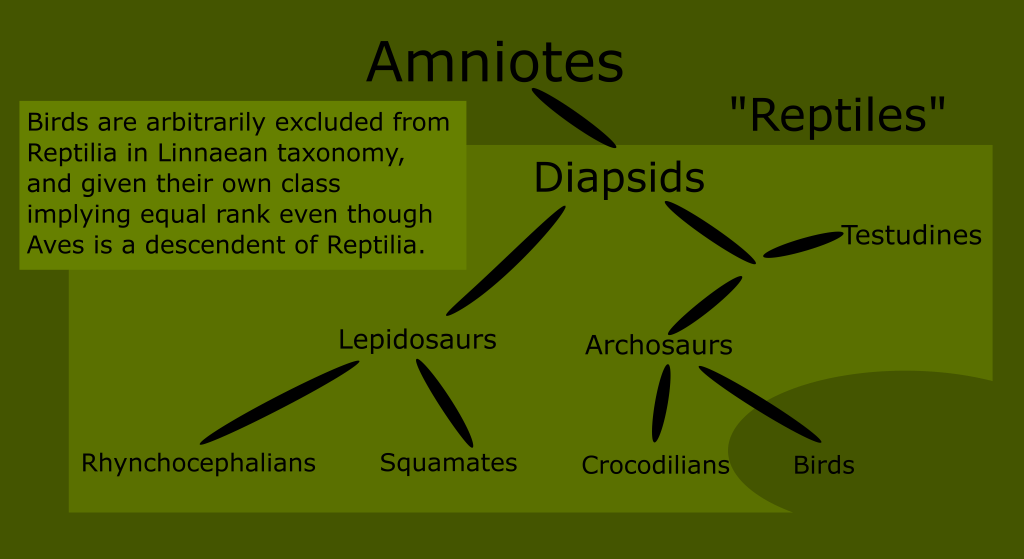

Here is the division of the clade archosauria, one of the two main branches of the reptile tree. You can see that the division including birds branches from a single point, and contains everything after it. This means that birds form a clade. For this reason the clade retains the name of the Linnaean class Aves to denote all birds, also known as avian dinosaurs.

You may hear a clade be referred to as “unranked.” This is a reference to the Linnaean system that may be more familiar to readers or researchers. What it means is that the clade is not equivalent to any Linnaean rank, and does not exist as a category in Linnaean taxonomy.

You can also see from this cladogram that birds are a subset of the groups making up the clade dinosauria, which makes birds a subset of dinosaurs. Not all dinosaurs were birds, but all birds are dinosaurs.

This illustrates another feature of phylogenetic classification, one that it shares in common with Linnaean ranks; every new clade continues to belong to every clade its ancestors did. Birds are a subset of dinosaurs, dinosaurs are a subset of archosaurs, which are diapsids, which are sauropsids, which are amniotes, which are tetrapods, which are chordates, and so on.

This is because the “nested hierarchies” or “groups within groups” nature that the Linnaean system revealed is a feature of life, and was one of the greatest strengths of the taxonomic system. One could say that Linnaeus’ innovation was “the grouping of groups” since he did not coin the terms “genus” or “species” but he did have the idea to create and group higher level classifications in such a way so as to smoothly unite all animals into a common category.

Another term this visual can illustrate is what is meant by a “sister clade”. You can see that Crocodilians are not dinosaurs, but they are archosaurs. Thus we would say that Crocodilians are a sister clade to dinosaurs. Pterosaurs are also not dinosaurs, although they are not shown on this diagram.

Another advantage of using phylogenetic trees for classification that would not have been available during Linneaus’ day is the use of molecular analyses to determine ancestral relationships.

This is the same kind of test used to determine family histories, or identify the parents of a child, although it is more difficult the more distantly related organisms are. Hence the name, phylogenetics; phylogeny (evolutionary history) based on genetics.

One final shortcoming of the Linnaean ranks was that many of them were paraphyletic. This means that the grouping includes a common ancestor, but only some of its descendants.

An example of a paraphyletic grouping is the Linnaean class Reptilia. (Although Linnaeus originally lumped reptiles in with amphibians, which only exaggerated this error.)

This would not have been known in Linnaeus day, since he and his colleagues only sought to classify extant species. This resulted in a view of life that had huge “gaps” or “jumps” in it. This is what I meant when I said that this early system was like a snapshot closeup of a small part of a much larger tree.

In this illustration, you can visualize the “low resolution” of the time. The unknown and extinct animals always linked the extant species back to the common ancestor of all animals, but this was a blind spot in Linnaeus day. As our knowledge has increased, we are able to see the relationships between these groups with greater resolution. Turns out there was a lot of information in that blind spot.

The more we learn, the more complete our knowledge the history of life is, and the fewer “gaps” and “jumps” exist among the animal phyla. In the 18th century, we were zoomed in on only the most recent tips of what we now know are distinct branches.

The closer we look, the more details there are between any given creatures, and its route back to the common ancestor of all animals. This chart leaves out vast swaths of creatures, opting to show only the simplest representation of the relationships between these phyla.

Not only are paraphyletic classifications completely arbitrary, they can be misleading, causing us to rank descendant groups as equal to their ancestors. Linnaean taxonomy provides a catalogue style system for filing different creatures into a database.

But in order to understand the history of life, and the evolutionary context of whatever organism you are looking at, you need a different suite of information. In the Linnaean system, groups may not only fail to intuitively reflect their ancestry, but may actually give the wrong idea entirely. This requires you to bring background knowledge to the table in order to keep track of where you are while using the catalog.

Technically, this causes the Linnaean system to become redundant in additional to being unwieldly. The use of monophyletic clades encodes the evolutionary history into the classification scheme itself such that learning taxonomy is learning phylogeny. This solution has a mathematical elegance.

Those Linnaean ranks that did constitute a clade, like Mammalia and Aves retain their name for the sake of simplicity. These familiar named clades can serve as something like a mile marker to help navigate the vast world of biodiversity, since the number of clades is astronomical.

This is one of the struggles of taxonomy. Biodiversity is so vast that practically infinite numbers of monophyletic clades exist, and are continually produced as populations continue to diverge from each other. Many of these clades are not named, so it helps to start with a familiar landmark, and navigate towards the group we want to look at depending on how specific we are being.

That being said, informal paraphyletic groups can still be useful for specific applications. For example, “fish” is another paraphyletic term, and even though it essentially means nothing in a taxonomic sense, the word is far from useless in the colloquial sense.

Hopefully this essay helped you understand what a monophyletic clade is, where Linnaean taxonomy is misguided, and why paraphyletic taxons can be problematic. I hope also that I have helped you see how evolutionary history and taxonomy are inseparably linked, as your understanding of one improves, so does the other.

In the next video in this series, I am going to go into more detail of the reptile family tree, expanding it to include extinct animals such as dinosaurs, pterosaurs, ichthyosaurs and evaluate the phylogenetic position of turtles. I hope you’ll join me.