From so simple a beginning

There is grandeur in this view of life…[that]…from so simple a beginning, endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Charles Darwin, 1859

Hello and welcome to Endless Forms. Today we are going to take a brief look at the history of taxonomy, that is the systematic classification of organisms, and begin to build an appreciation for how it contributed to the discovery of evolution. This will also serve as an introduction to this channel. I’m pretty new to this, so any feedback on what I can do to improve the content for future installments is appreciated. It is my hope to introduce you to your world as you’ve never seen it before, and to do my part in raising awareness of conservation. So without further ado, let’s get started.

In the early 18th century a Swedish naturalist by the name of Carl Linnaeus set about the task of cataloging all life. He was not the first to attempt this, but he was the first to create a system of consistent names and organization that was widely applicable to the world of living things. Linnaeus’ approach to classification revealed a deep pattern in nature. This is why he titled his work, Systema Naturae: or the system of nature.

Prior to Linnaeus’ work, previous taxonomies were much more superficial and anthropocentric, projecting equivalents of human social structures and religious notions onto nature.

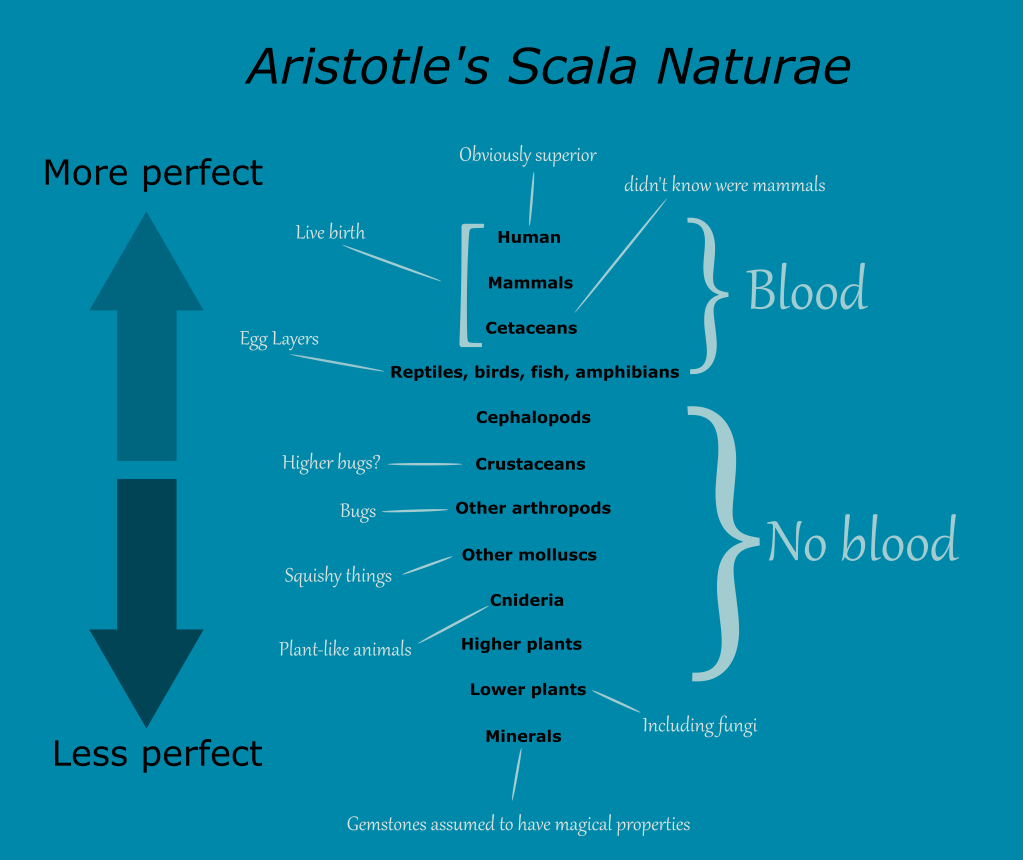

Aristotle developed the concept of ranking the living world vertically according to what he perceived to be “higher” and “lower traits.” This formed the basis of the early status quo for taxonomy, Aristotle’s ladder of nature formally known as Scala Naturae.

Generally, the more aware and mobile an animal was, the higher it was placed on the ladder, ultimately culminating in man. Similarly, plants were ranked below animals, with flowering plants ranking above “lesser” plants (a grouping which also included fungi.) The bottom of the ladder was made up of the various known minerals and materials and was seen as the lowest form of being, such that everything was part of a spectrum of existence.

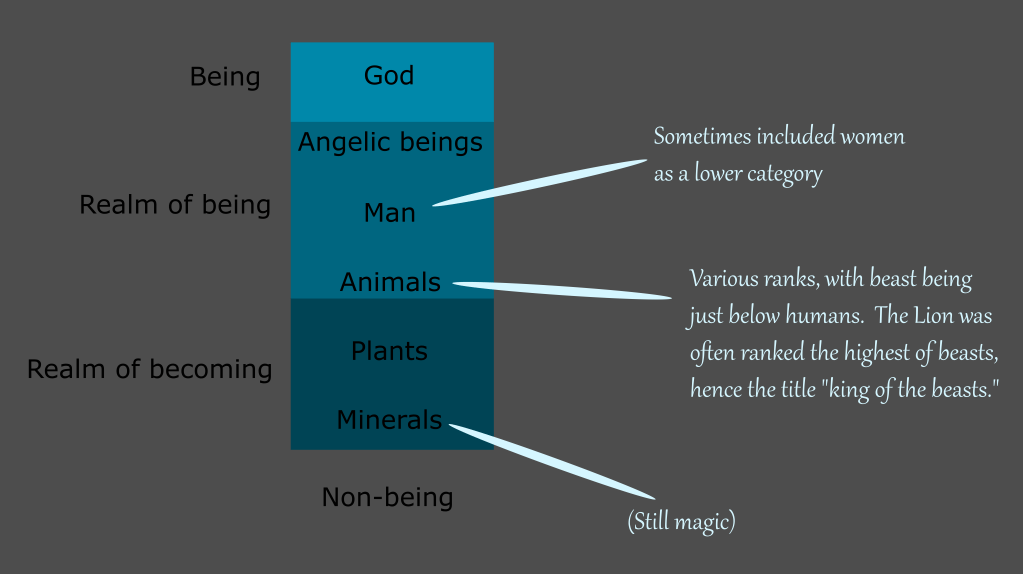

This vertical arrangement of life was later adapted during the middle ages and became known as the Great Chain of Being. This version of the ladder retained the previously discussed organization, but added angels above man, and the Christian god as the top and origin of the chain. Some iterations also included the social hierarchy among humans as well. Subdividing the human part of the chain into royals, nobles, peasants, and so on.

This arrangement of the world was assumed to be divinely decreed and thus unchangeable. This is one reason many people accepted their place in the world and tolerated an unfair society. For the same reason, naturalists in Linnaeus’ time assumed that individual creatures, or species, were immutable, stand alone creations; that is to say that a creature’s place in the hierarchy of the world was immovable. In addition, this view also contributed to cultivating the intuition that extinction was impossible; the very idea of gaps in the chain was absurd.

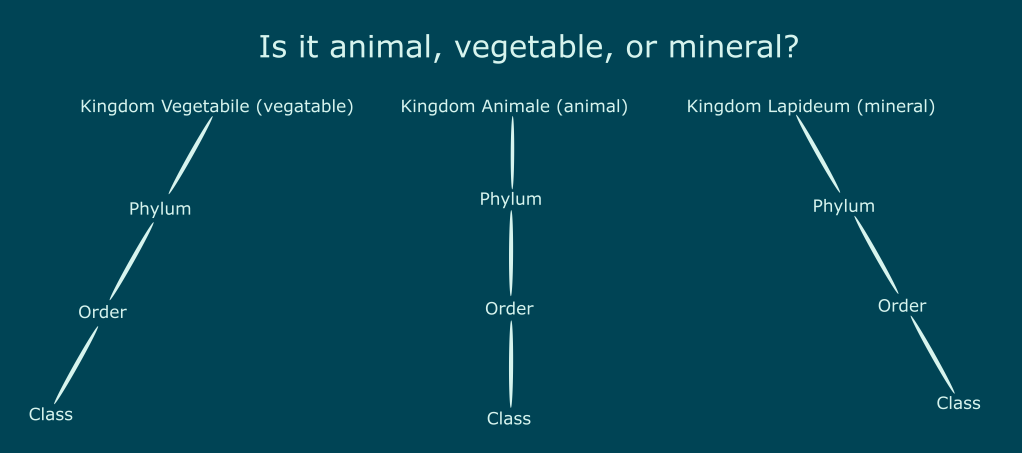

Taxonomy, therefore, was only a matter of identifying these tiers of life, and then the different species within them. Linnaeus also initially subscribed to this view, and based his original three divisions of life on it. He initially divided the world of living things into three groups called kingdoms; one for plants, one for animals, and one for minerals.

Eventually it was realized that his work as a whole hinted at something deeper, something he had not expected to find. Linnaeus had inadvertently revealed that this view of life as a linear hierarchy was fundamentally flawed.

His system of classification differed from previous organizations of the natural world by basing its divisions on traits that often turned out to be homologous, rather than analogous. What this means is that while previous taxonomies may have grouped bats and birds together as an informal group of “flying things that aren’t bugs” Linnaeus was able to recognize bats as mammals, rather than group them with birds just because they both have wings and can fly. Their wings are analogous because they are structures used for the same purpose; powered flight. But this doesn’t make them the same thing. The wings of insects are also analogous to those of birds and bats, but it was obvious that there were more fundamental traits separating birds, bats, and bugs and that it would be absurd to lump everything with wings together for this reason alone.

Linnaeus wanted to classify organisms by what they were, not what they did or where they lived. For this same reason, he was also among the first naturalists to recognize that whales are mammals. He wanted his system of taxonomy to reflect natural categories, rather than invent arbitrary distinctions just for the sake of naming things. He wanted to see how it all fit together in the grand scheme; to see the big picture. His contribution to science extends beyond mere nomenclature. While his intent was to create a convenient and consistent naming system for the myriad creatures known to science, his system had revealed an interesting pattern.

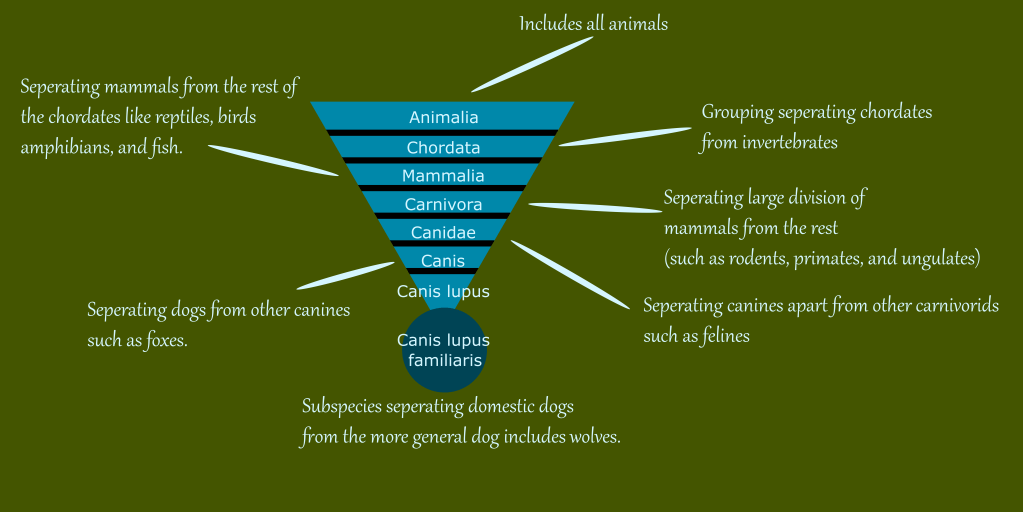

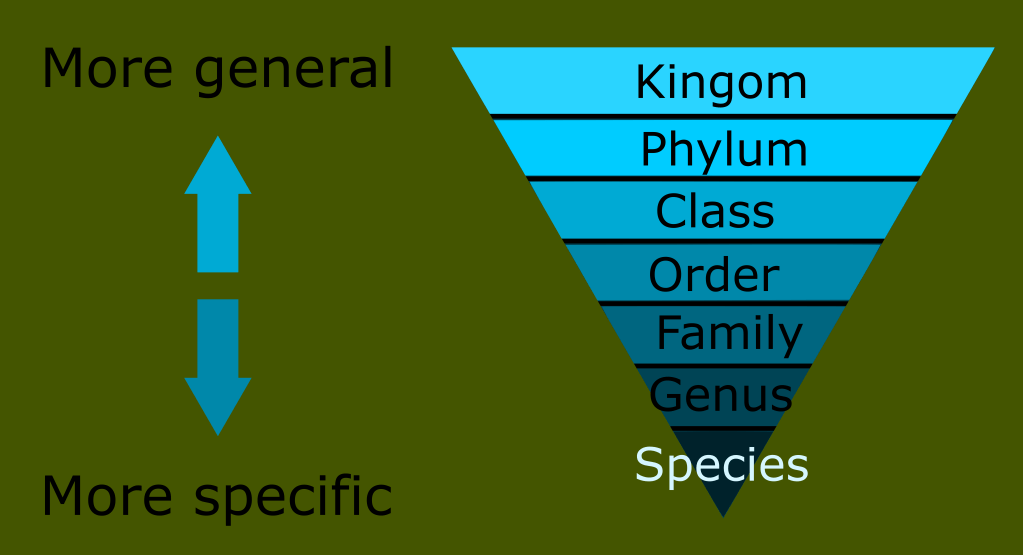

Linnaeus’ system revealed that life can be organized into a series of nested groups, with each higher group including everything in the lower one, until all animals converged into one kingdom, and plants (with which he grouped fungi) into another. For example, let’s look at a simplified version of the taxonomy of the domestic dog. The kingdom Animalia contains all animals.

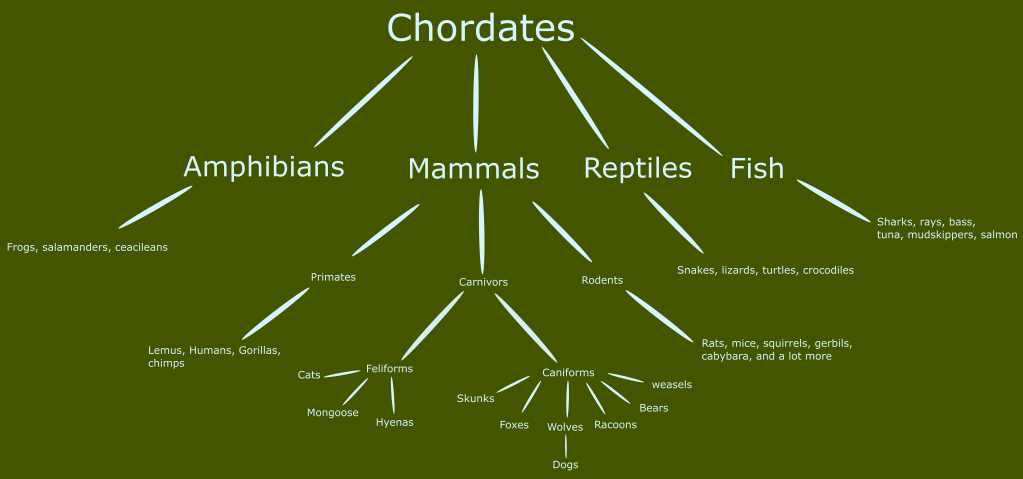

The kingdom splits into animals with, and without a spinal cord. Chordata represents all animals with this feature. Chordata further splits into several groups including reptiles, amphibians, birds, fish and mammals. Mammalia splits into several groups including primates, ungulates, rodents and carnivores. Carnivora splits most broadly into felines and canines. Canidae further divides dogs and wolves from foxes in the genus Canis. The species name Canis Lupus includes both domestic dogs and wolves. The subspecies Canis lupus familiaris denotes our beloved domestic dog breeds.

Note that each level becomes progressively more specific, and split into more subdivisions than the last category above it. This upside down triangle is intended to show how Linneaus’ classification works from more general, to more specific to provide a reference point for all groupings.

But if you read it backwards, you can see that every organism belongs to a much larger parent category which itself belongs to a larger category with each group bringing more groups with it like the branching of a tree.

Even in this dramatically simplified diagram you can see how quickly the categories scale. I could only fit so much on the screen, but this pattern continues to place all animals together in a single kingdom uniting everything from slugs and bugs, to man and puppies. If this reminds you of a family tree, it should because that’s what it is.

It is important to note that Linnaeus’ approach was fundamentally different than previous ways of thinking about taxonomy. While the great chain of being presented a linear structure of nature, with all creatures being ranked vertically relative to either man or god; Linnaeus’ new paradigm compared organisms to each other in a divergent pattern, thus breaking the artificially conceived linearity in the natural world.

It was precisely because of his insight into the fundamental structure of organisms that Linnaeus’ taxonomic system reflected their ancestry, although he did not realize this. His discovery that life can be organized into a series of nested tiers of fundamental similarity gradually diverging into more diverse and specific organisms created entirely new kinds of questions.

Why does life fit so well into a nested hierarchy of gradually diverging traits? Why do the lines between these groups break down when one looks closely? Why is there no naturally implied classification for man apart from the great apes? Most potently of all, he was troubled in later life by the fact that through hybridization of plants he could generate what appeared to be new forms. What did this mean? Were new species a possibility? Did they occur naturally, apart from the fiddling of man?

In addition to facilitating the discovery of these new lines of inquiry, Linnaeus was also a firsthand observer of another discovery of the age; that life was almost infinitely more diverse than previously thought. Linnaeus lived in an era of intense exploration of the world. One benefit of this was the near constant flow of new creatures being discovered, especially from the new world.

Much of the previous extent of taxonomy was limited by the diversity of local wildlife; naming the organisms large enough, and common enough to be noticed by the average person was a relatively straightforward task. For example, any local people had names for large mammals such as bears, horses, camels, dogs, cats, and would have names for plants and insects of agricultural significance. But the vast majority of biodiversity was relatively unknown to most people.

But during this era the sheer overwhelming diversity of life was being revealed. From the discovery of microorganisms a few decades earlier, to the innumerable arthropods, bizarre and exotic birds, and the emerging awareness of the existence of the great apes, the world of living things was much larger than had ever been appreciated. In the light of the extent and scale of the world of living things, the chain of being began to look as childish and naively conceived as the geocentric model of the universe had already been shown to be.

Linnaeus had indeed succeeded in his goal of revealing the big picture of the system of nature, at least as far as biology was concerned. But what did it mean? Sadly, he did not live to find the answer. It wasn’t until a century later that another naturalist would open the door to understanding the fundamental relationship all life shares.

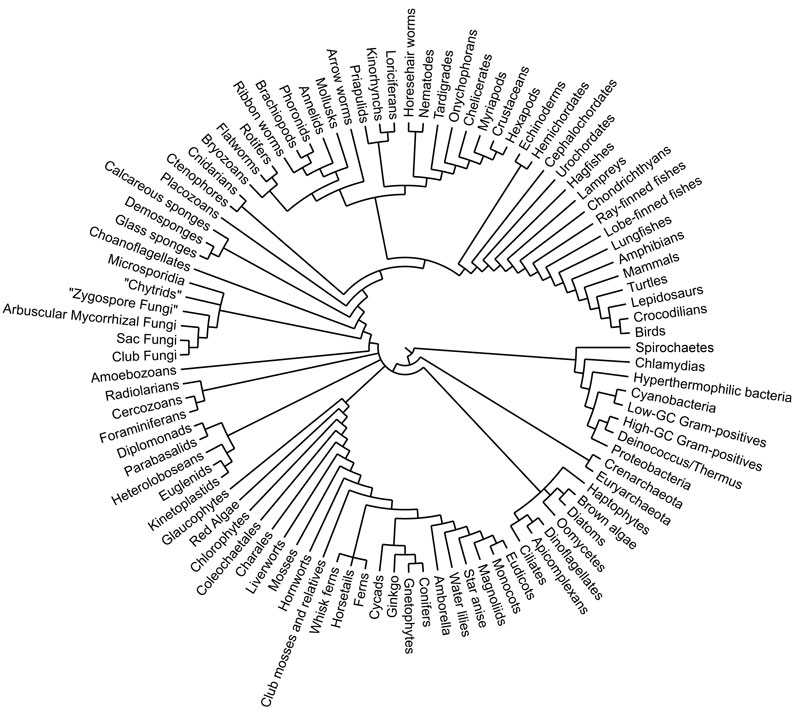

With the foundation laid down by Linnaeus, Charles Darwin, and other naturalists of his era, realized that the overwhelming and often convoluted diversity of life was indeed comprehensible. With the discoveries of common ancestry, speciation, and natural selection; Linnaeus’s mysterious nested hierarchies suddenly made perfect, elegant sense. In a way, biology had found its unified field theory. Something that tied it all together and made the world of living things make sense as a whole.

Even over 100 years later, many still do not appreciate the scale of biological diversity. Which is unfortunate, because we are destroying it at an alarming rate.

I suspect this failure to appreciate the other forms of life in our world is twofold. First, it seems few appreciate just how diverse life is. Ask the average person to name five animals; the answer will most likely be five chordates at least, if not all tetrapods like mammals, reptiles, or amphibians. But life is so much more diverse than the few familiar forms one might take little Timmy to the zoo to see.

There are a myriad of creatures that defy familiar conceptions living in the soil beneath your feet, in the air around you, and in the case of my childhood; the drainage ditch behind the Library parking lot.

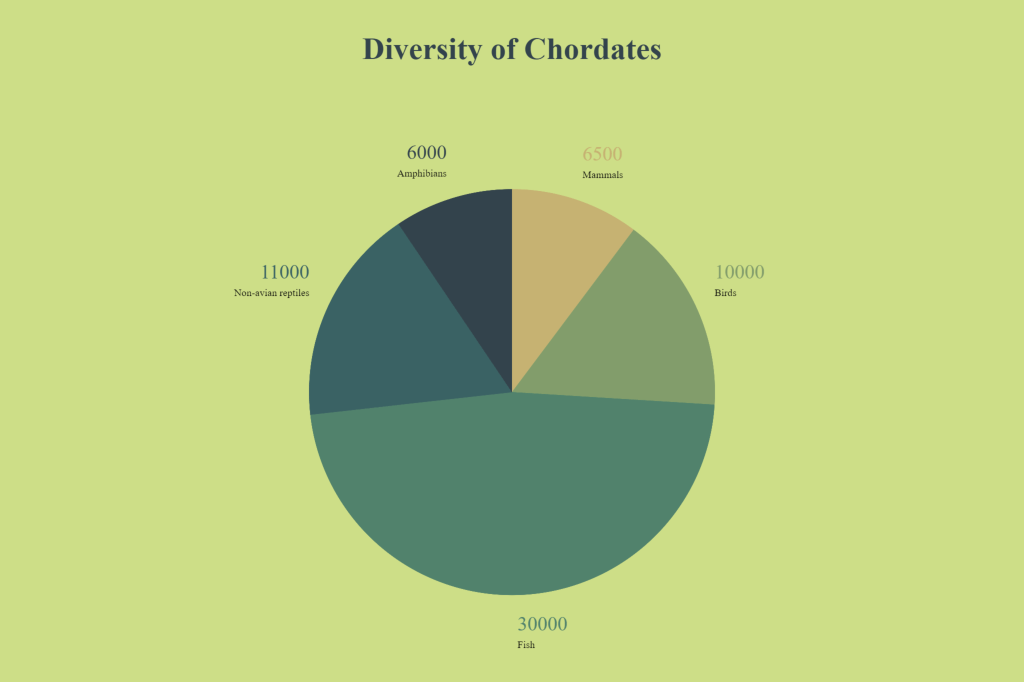

Mammals are probably the most familiar group to us humans, this makes sense since we belong to this group as well. Think about all the mammals you know of. From the magnificent tigers of India, to the infamous rodents, to the beloved dolphins, and elephants. Even this group is more diverse than you might realize. A full 40% of mammals are rodents. From the familiar mice and rats, to the mysterious bats, to the lesser known Capybaras rodents are the largest group of mammals. There are around 6500 or so described species of mammals right now.

For birds, the number of described species approaches 10,000. From the stealthy owl, to the swift osprey, adorable ducks, glorious hummingbirds, bizarre kiwi, familiar chickens, to the myriad finches, from brainy parrots, to the imposing cassowary birds are one of the largest groups of chordates.

There are around 4800 frog species on record at the moment. From ceratophryds, to the familiar ranids, to the warty bufoids, the acrobatic hylids, the unsettling surinam toad, and the enormous goliath, frogs are a diverse and successful group with many unfamiliar forms. They represent nearly 90% of extant amphibians which include another 1-2 thousand species.

From the staggeringly successful colubrids, the ancient boas, the innovative pit vipers, and the lesser known serpents, snakes represent another 3000 plus species. Other non-avian reptiles including testudines, crocodilians, rhynchocephalians, and the rest of the non-snake squamates pile on another 8000 or so species.

The huge and diverse range of (mostly) aquatic organisms loosely referred to as fish are represented by the main divisions Agnatha such as hagfish and lamprey, Chondrichthyes which encompasses all cartilaginous fishes ranging from the graceful rays, elegant sharks, and finally the monstrous Osteichthyes or bony fish including everything from bass, salmon and tuna, to frogfish, anglers and mudskippers. Adding the conglomeration of fishy things to the list piles on another 30,000 or so species.

All of these represent the clade Chordata. Every shark, gecko, toad, treefrog, mouse, pony, puppy, kitten, gorilla, person, skink, kingsnake, stingray, rat, gopher, lemur, salamander, porcupine, hedgehog, possum, racoon, caecilian, turtle, chameleon, frogfish, clownfish, catfish, lungfish, tiger, leopard, cheetah, giraffe, tortoise, virtually every non-arthropod animal you can think of is a chordate.

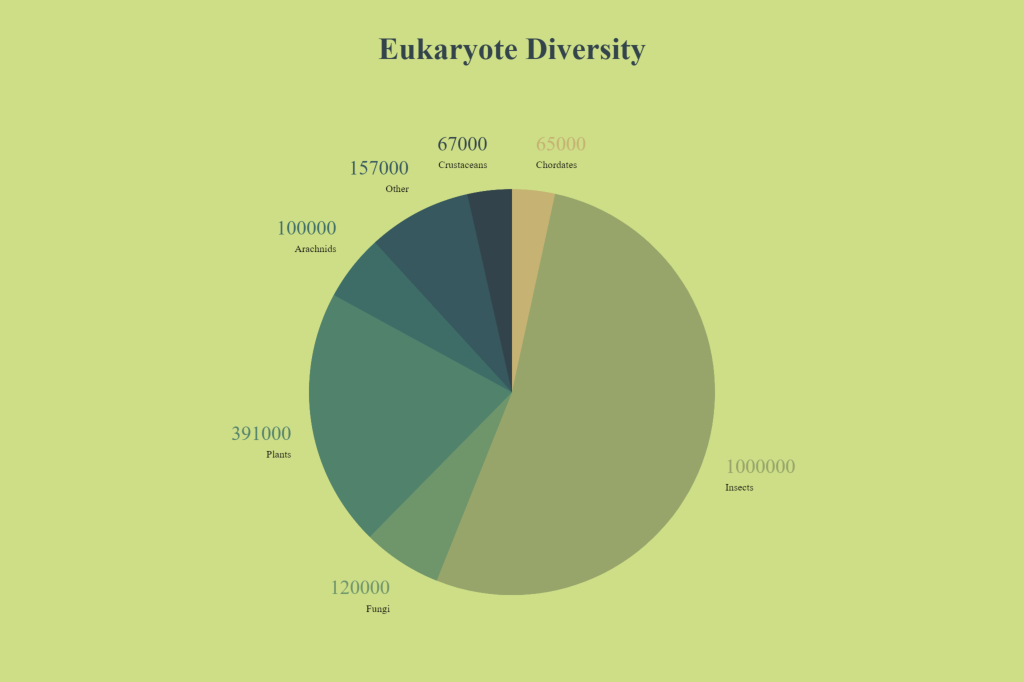

But chordata only represents only a tiny sliver of all extant species. Every familiar animal fits into this tiny sliver bordering insignificance. Even this graph has been simplified to make it more accessible to the uninitiated in the staggering world of biodiversity.

If we throw the fossil record into the mix, and include all of the extinct species we are now aware of, the range of diversity of life becomes truly astronomical. It is estimated that the species living today are only a small fraction of all the diversity that has existed during our world’s long and rich history.

Each and every creature that exists represents an unbroken line of reproduction reaching back around 2 billion years. This includes you. You are part of an unbroken chain reaching all the way back to the first life. Not one of your ancestors failed to reproduce, or you would not be here. You carry on a grand tradition going back eons.

Appreciating all of this sheds light on why places like the amazon rainforest are so valuable. Not only is it an important source of oxygen and a reservoir of carbon, but it is a museum of myriad artifacts of evolutionary history. The sheer number of species in this region has hardly been probed. This incredible ecosystem is the result of a forest being left more or less undisturbed for 50 million years. How much history is lost when it is destroyed?

This leads me to the second reason for the lack of appreciation for other species. The first was that people just don’t know about them. The second is like it; modern life keeps us so busy, so focused on money and convenience that we forget what we are, and where we live.

This site is dedicated to exploring the vast diversity of life, extant and extinct, to help you develop an appreciation for the wonderful world we are privileged to call home. In doing this, it is my hope that you will come to appreciate, and value living things as you never have before. I hope also that in developing an appreciation for our shared home, you will take to heart that we, humans, are not the only ones who live here, and our vast influence demands that we have a responsibility to use it wisely and sustainably.

So join me as we explore life, in endless forms most beautiful.