When I was a child, my favorite animals were reptiles and amphibians. I spent countless hours collecting toads under the street lights at night, chasing whiptails in the sun, racing to grab spiny lizards before they darted up the tree, all while seeking the holy grail of childhood herping: snakes.

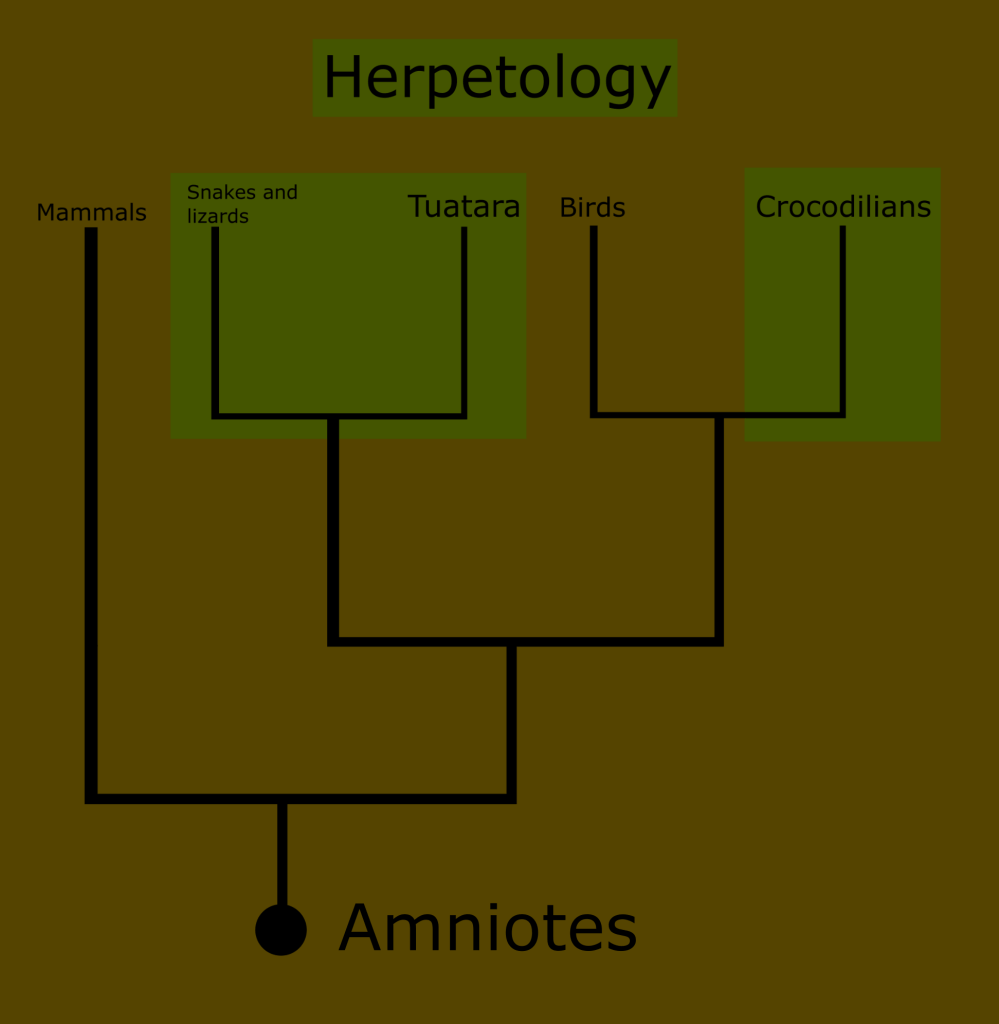

Reptiles and amphibians just seemed to fit together. Of all the terrestrial chordates, they alone were cold blooded. They were discussed in tandem books and documentaries, and they were even lumped together under the scientific discipline of herpetology.

Something about these magical creatures captivated my young mind. Years before I ever met my first scorpion or tarantula, I had known my first love.

Reptiles and amphibians tend to elicit extreme reactions in people. People seem to either hate, say frogs or snakes, or love them with little middle ground. Collectively reptiles represent some of the strangest, and yet most familiar of all animal groups. Love them or hate them, everyone knows a snake when they see it.

However reptiles are not limited to the modern familiar forms, they also include the famous dinosaurs that every young child spends a period obsessing over.

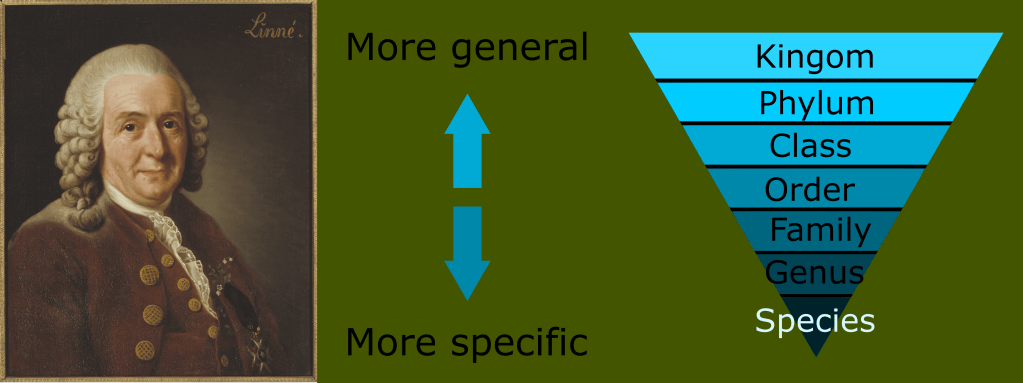

Reptiles, as we normally think of them, are not so easily classified as “cold blooded scaly things that aren’t fish.” To see why, we should start by looking at how reptiles were initially classed in the Linnaean system, and how our understanding has grown over time. So join me, as we explore life in endless forms most beautiful.

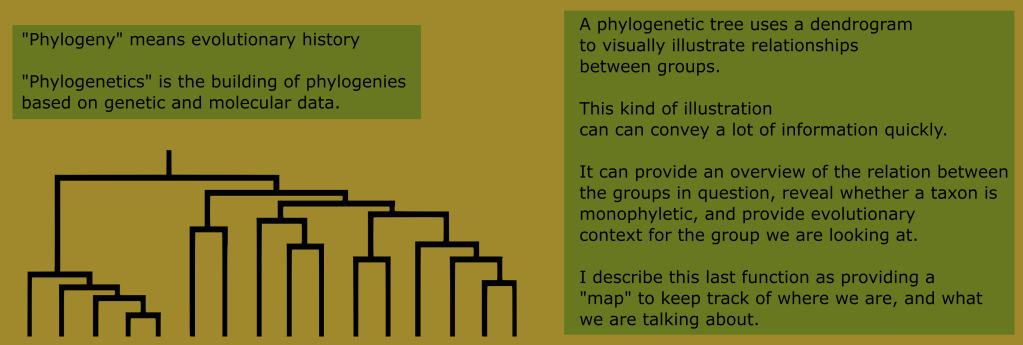

In the last entry in this series on taxonomy, I introduced the concept of monophyletic clades for classification, in contrast to the historically traditional Linnaean ranks. Today, I want to look at the history of the classification of reptiles and amphibians, and begin to take a closer look at the reptile family tree.

When Linnaeus published the first edition of Systema Naturae in 1735, he had initially lumped reptiles and amphibians together into sort of a “catch all” class he called Amphibia. Because he lived in Sweden, which has a very low diversity of reptiles compared to the southern US where I live, he knew comparatively little about them.

This first edition included only a handful of described reptile and amphibian species totaling 27. Even though the Linnaean group “Lacerta” included lizards, crocodilians and salamanders, the fact that he created two additional groups for the other tetrapod herps, Rana for frogs and Testudo for turtles did reflect the growing awareness of greater diversity within the Amphibia which would later be built upon.

As a side note, it turns out that Linnaeus intensely disliked the animals he grouped as the amphibia, often ironically expressing gratitude that they had a low diversity compared to what he saw as more noble classes like mammals and birds. He stated in the 1735 introduction to the class: “The Creator in his benignity has not wanted to continue any further the Class of Amphibians; for, if it should enjoy itself in as many Genera as the other Classes of Animals, or if those things were true that the Tetralogists have fabricated about Dragons, Basilisks, and such monsters, the human genus would hardly be able to inhabit the earth.”

Also note from that quote his distaste for mythological animals. This is an important part of Linnaeus’ mindset that was deeply influential on the field of biology, more on that in another entry.

By 1740, with the second edition published Linnaeus had divided the Amphibia into two orders; the Reptilia or the amphibians with legs; which included frogs, turtles, salamanders, lizards, and crocodilians; and the order of legless amphibians he called Serpentes which included snakes, as well as legless amphibians.

Eight years later, the sixth edition (which was technically the third edition directly authored by Linnaeus) saw a dramatic increase in diversity among the described amphibians, including 6 new genera, and 40 new species.

Notably, by this time, Linnaeus had developed something of a love-hate relationship with snakes that would last the rest of his life. Having both worked as a physician and dedicated some time to attempting to find new remedies for snake bites, Linnaeus apparently developed a fascination with snakes. By the sixth edition, he now drew a clear distinction between Colubrids and Vipers.

Finally, in 1758, after spending a few years traveling, lecturing and further refining his work, Linnaeus would publish the largest update to Systema Naturae to date, and the single greatest increase for the class amphibia in the entirety of his work. The 10th edition of Systema Naturae would add another 117 described amphibia to the list, as well as introducing another order for a handful of cartilaginous fish he called Nantes.

In it Linnaeus reveals that his opinion has not changed much regarding the class amphibia, stating: “These most terrible and vile animals are distinguished by their unilocular and single chambered heart, arbitrary lungs, and divided penis. Most amphibians are rough, with a cold body, a ghastly color, cartilaginous skeleton, foul skin, fierce face, a meditative gaze, a foul odor, a harsh call, a squalid habitat, and terrible venom. Their Author has not, therefore, done much boasting on their account.” I rather disagree, but to each their own I suppose.

The final edition of Systema Naturae authored by Linnaeus was a large update to the work as a whole, but relatively unremarkable in terms of his treatment of the amphibia.

Linnaeus had made some interesting insights in his work of classifying the natural world. In the first edition, whales were grouped with fish, but he corrected this in the 10th. He was also one of the first to remove bats from being classed among the birds because he recognized their mammalian nature.

But for all his insight, he seemed only dimly aware of the fundamental natures of what we now call reptiles and amphibians. To be fair, Linnaeus was primarily a botanist as his main area of expertise.

Still, the Linnaean system had treated the amphibia largely arbitrarily, basing the classifications on the number of limbs more than anything else. For example, in 1776 naturalists were perplexed by the existence of an animal that defied categorization in his normal treatment of the animal world, the Siren.

Such was the fascination with the animal that some of Linneaus’ correspondences were printed and distributed as a dissertation on the siren. Linnaeus describes it thus: “It is shown to us how the animal diverts from the general characterizations in the Animal kingdom; in lack of hair and feathers it can be neither Mammal nor Bird; among Amphibia it cannot be assigned to any of the known divisions, neither to the Reptilia, which have four feet and no gills; nor to the Snakes, that are without feet, fins and gills; nor to Nantes, which all have fins. In view of this, Author shows the necessity of establishing a new Order in Reptilia, with two feet, lungs and gills. Many would think this animal is simply a larva of Lacerta Iguana or another, but both claws and its sound deny this…”

His reference to the larva of an unambiguous lizard reveals that Linnaeus had not truly understood the difference between salamanders and lizards, like iguanas.

He was aware that some of the amphibia undergo metamorphosis, and others are born or hatched as miniature adults, but it would seem he had not developed an appreciation for the implications here.

The distinction in reproductive modes of the group was noted in the introduction to the tenth edition as follows: “A polymorphous nature has bestowed a double life on most of these amphibians: granting that some undergo metamorphosis and others cast off their old age. Some are born from eggs, whereas others bear naked young. Some live variously in dry or wet, whereas others hibernate half the year. Some overcome their prey with effort and cunning, whereas others lure the same prey to their jaws as if by magic.”

Despite this awareness of the dramatic difference in reproductive processes, the distinction between the Rana and the Lacerta was the presence or absence of a tail. Ranids, or frogs, were naked (scaleless), four legged reptiles that also lacked tails, and Lacerta, defined by having four feet and tails, were collectively called lizards. This included both the crocodilians and salamanders.

The latter were considered to be a subset of “Naked aquatic lizards with unarmed or un-clawed feet.” For all his detailed and intricate descriptions, Linnaeus’ treatment of the class amphibia remained superficial.

For many naturalists, the amphibia were just a collection of ugly and unappealing animals of varying levels of venom, disease, superstition, and were generally seen as varmints.

The biggest reason for this was the human tendency to see the world anthropocentrically. Of all the terrestrial animals, the amphibia are the least like us. Cold blooded, not soft and cuddly like birds and mammals, they seem the most alien to us despite being the majority of terrestrial chordate diversity.

But it is the amphibia that have more to teach us about ourselves than any other animal group. In learning about them, we came to understand what we are, and to see our true place in the world.

So what does distinguish what we now call reptiles from amphibians? To answer this question, let’s continue tracing the history of their classification.

The name reptile derives from the Latin word for crawling or creeping. In Linnaeus’ time the name was interchangeable with amphibian. While Linnaeus used the name amphibian, it is important to keep in mind that Reptile was the more popular term among French naturalists, but both referred to the class Amphibia during this period.

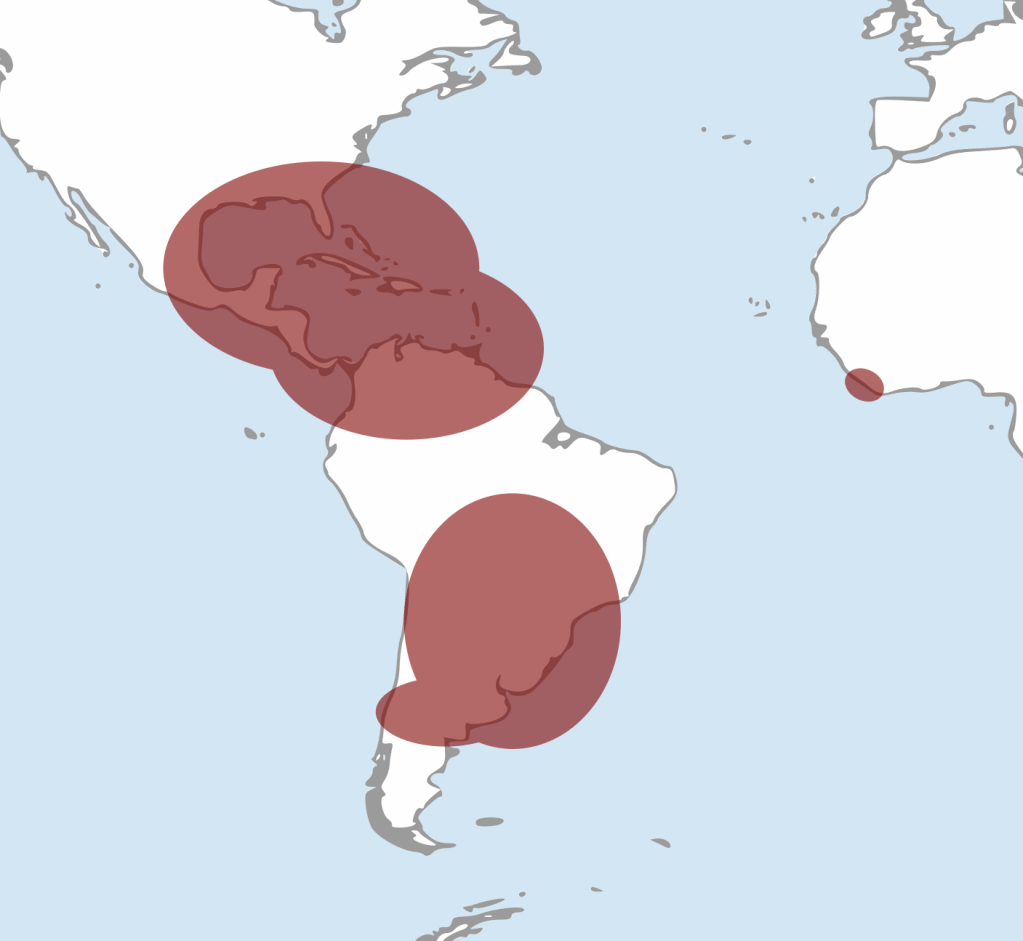

At the beginning of the 19th century a French geologist by the name Alexandre Brongniart published a paper titled Testing for a natural classification of reptiles in which he recognized the dramatic differences that set the frogs and salamanders apart from the rest of the reptiles, and proposed a new name for them: Batrachia.

(As a side note, frogs and salamanders actually do form a monophyletic clade within the amphibians and that clade still bears the name Batrachia to this day.)

A couple of years later a prominent entomologist by the name of Pierre Andre Latreille, would concur with this classification, and would opt to classify the Batrachia apart from reptiles entirely, making him one of the first to fully comprehend that these are fundamentally different groups.

As things played out, the new class would take on the name amphibia, as distinguished from the Reptilia which contains the remainder of Linnaeus’ original class, minus the cartilaginous fishes sometimes included. This brings us to the modern arrangement of reptiles and amphibians as wholly separate categories we are used to.

Of course, such a large taxonomic revision would take time to become widely used, but the amphibian class had some powerful advocates including Thomas Huxley, and Earnest heckle.

The distinction that Brogniart and Latreille based their revisions on, and upon which the advocates who concurred converged, was their fundamentally different mode of reproduction.

Amphibians, as we now define them, go through an aquatic larval stage of development after hatching. This mode of reproduction is similar to how many fish (to which the basal chordates belonged) reproduce.

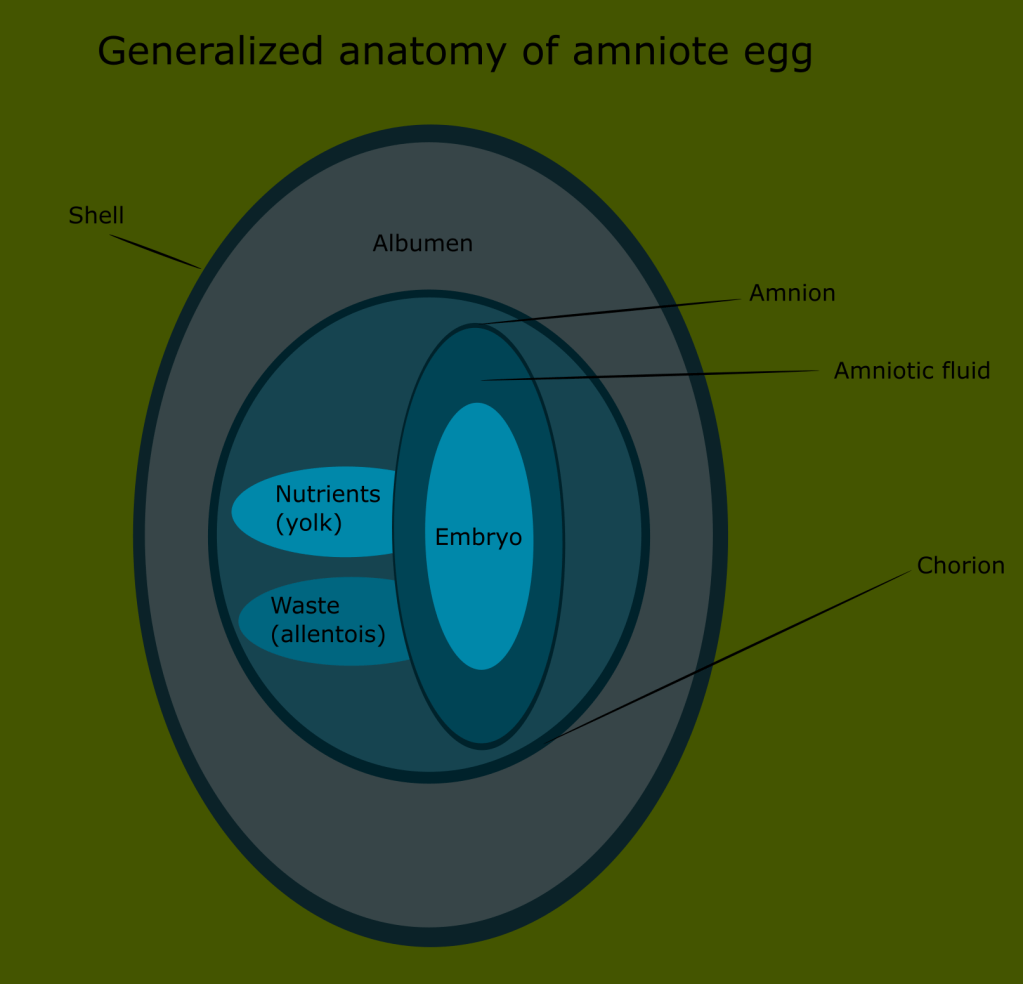

Reptiles on the other hand, are able to bypass the larval foraging stage. Instead, the embryo is able to develop inside the egg before hatching, thus reducing the threat of predation and removing the burden from the larva of needing to seek out its own food.

This is made possible by the presence of a membrane called the amnion. The development of this trait made it possible to reproduce on land, far from the bodies of water that amphibians depend on.

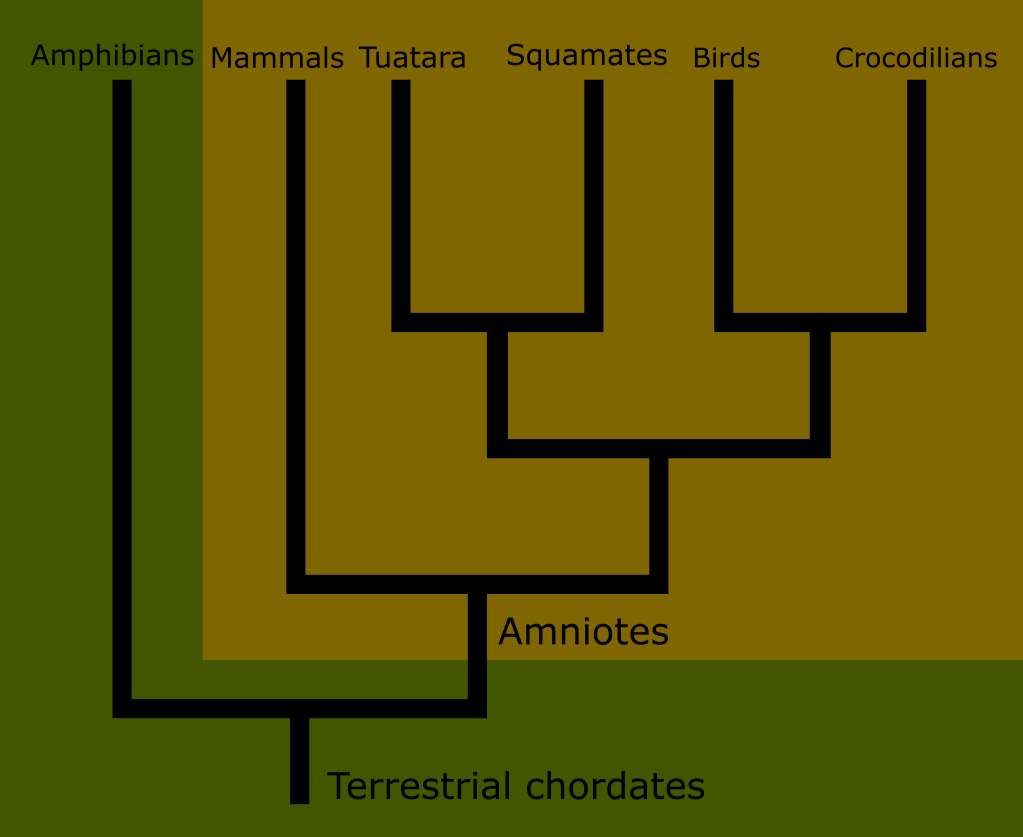

More importantly, it is a trait shared with all other terrestrial chordates, minus the amphibians. This meant that reptiles were more closely related to mammals and birds than to amphibians.

This more insightful distinction in classification would find widespread acceptance among naturalists during the early 19th century. This gives us our familiar land animal groups; mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians.

Things became more complicated with the emergence of paleontology around the beginning of the 19th century, and even more so by a series of developments in biology, culminating in the confirmation of common ancestry for the origin of species in the latter half of the century.

With the discovery of the first dinosaurs, and the budding field of embryology, the question was being asked what the relationships were between large taxonomic groups.

The realization that the world hadn’t always existed in its present form had come some time earlier from the field of geology, but even in Linnaeus’ time it was beginning to be realized that the same was true of the network of life as well.

Linnaeus himself became suspicious of the assumption of the fixity of species, or more correctly the fixed number of species, as he experimented with plant hybrids near the end of his life. He famously left out a line from his observations in the introduction to the 12th edition which assumed a constant number of extant species.

In another work, he also wrote about a species of thalictrum that he hypothesized to be a daughter species derived from a parent and as he put it “it seems to me to be the product of its environment/the daughter of time.”

While the conversation about evolution would become a hot topic among naturalists leading up to the point when Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, building upon the work and insights drawn by others like them, would finally solve the puzzle of the primary mechanism of evolution, it was already known in the 19th century that some species had existed in the past, that do not presently exist.

This raised the question of how these extinct animals should be classified. Which would have been a straightforward task if not for one thing: many of these paleo creatures belonged to groups that do not exist now.

Try to picture this. Naturalists of the time were well familiar with the modern classes of tetrapods; birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians. But as more paleofauna were discovered, the question “which group is it?” had to be answered with “none of the above.” The implications were staggering and stranger than previous conceptions of the world’s history.

A similar thing had happened to Linnaeus with the Siren, but it seems he was content to simply create a new category for the animal, without stopping to wonder why or how such a thing existed in the first place.

However this approach of creating a new category to accommodate each new type of creature would never work for the early paleontologists.

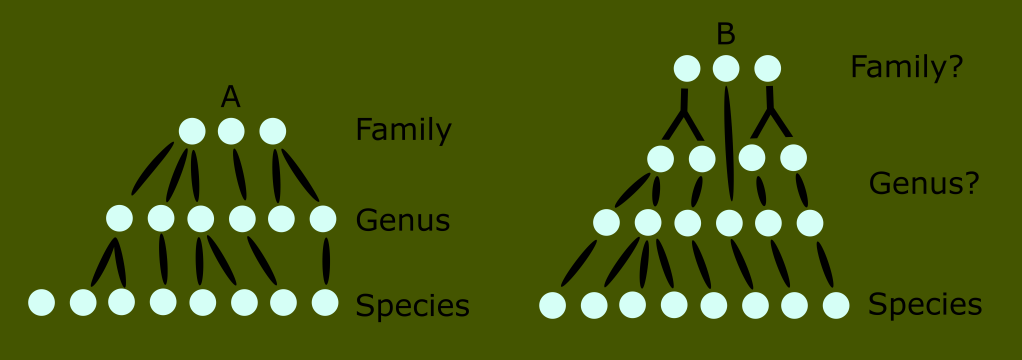

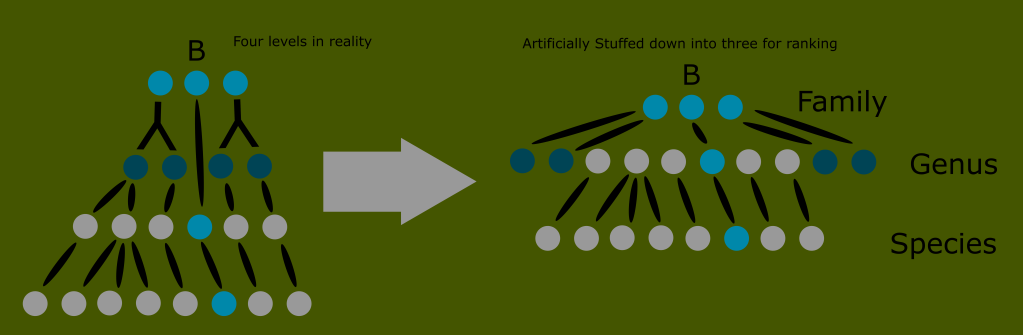

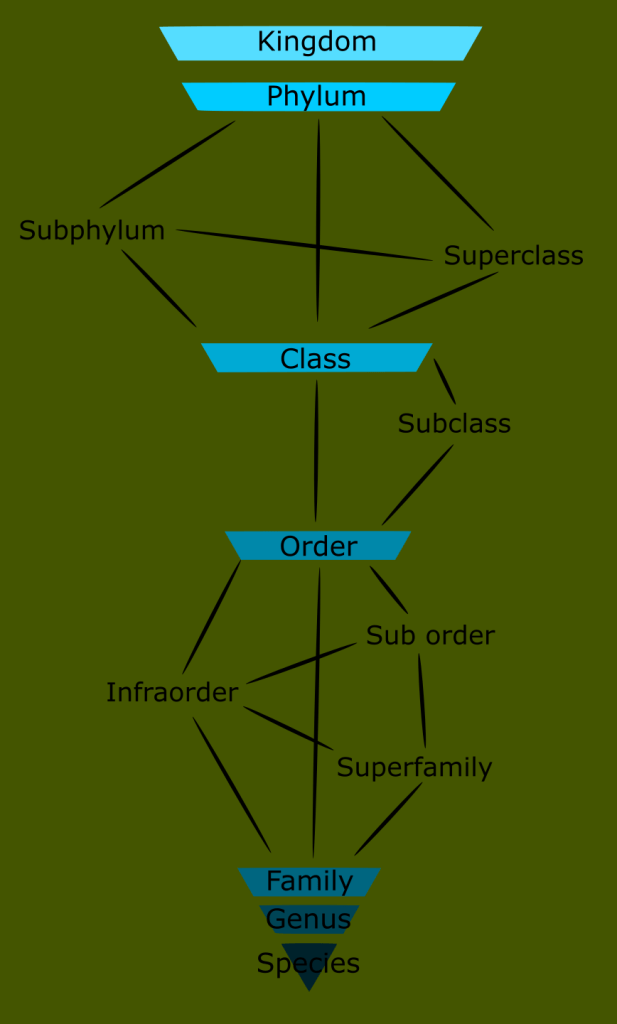

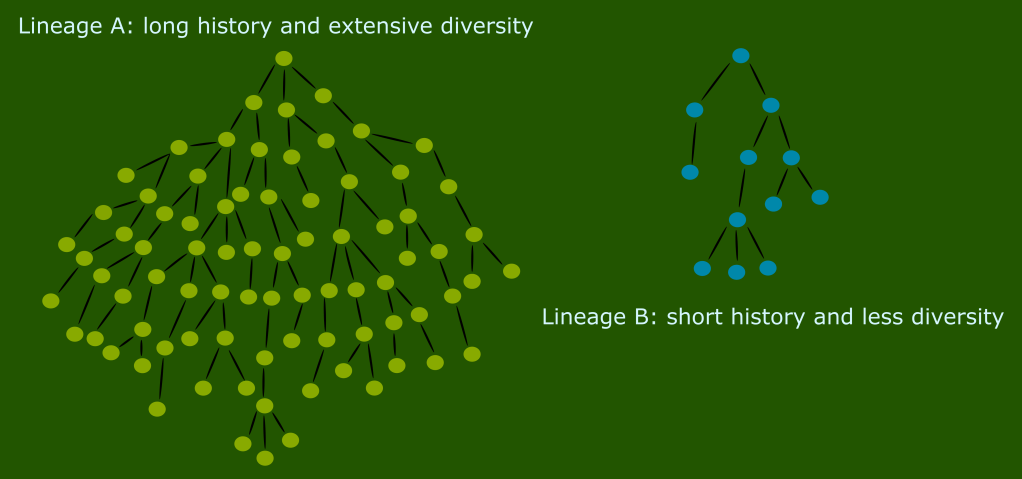

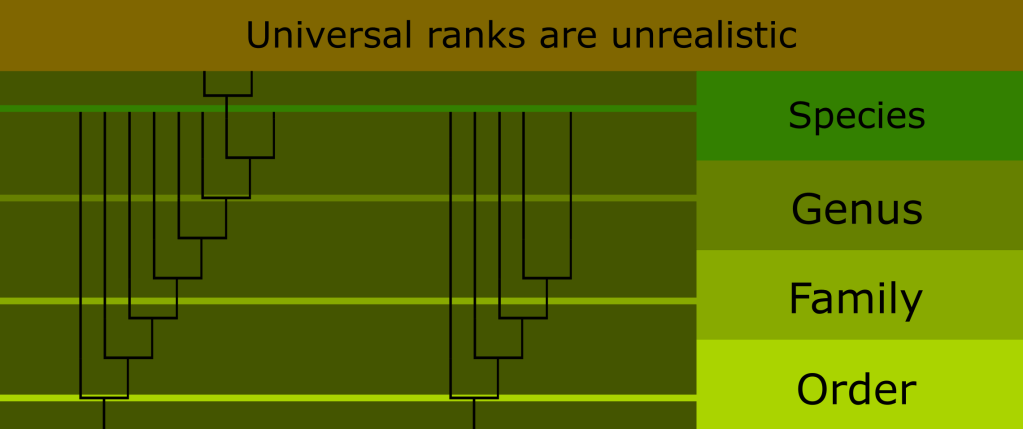

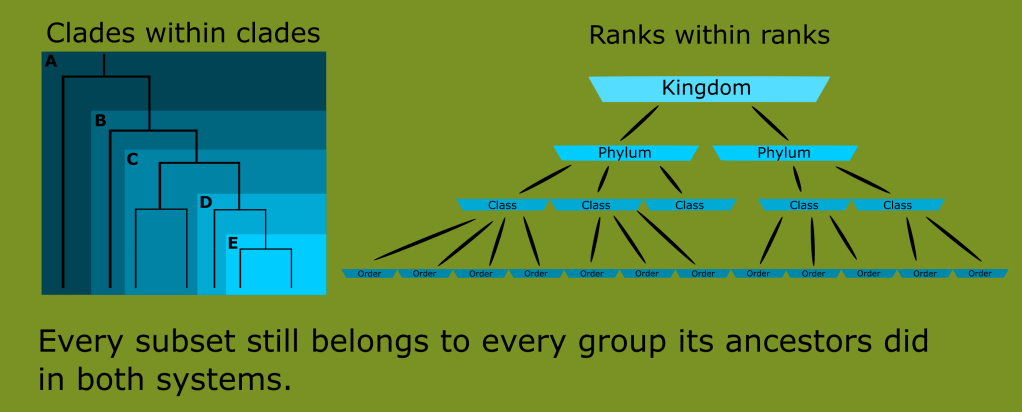

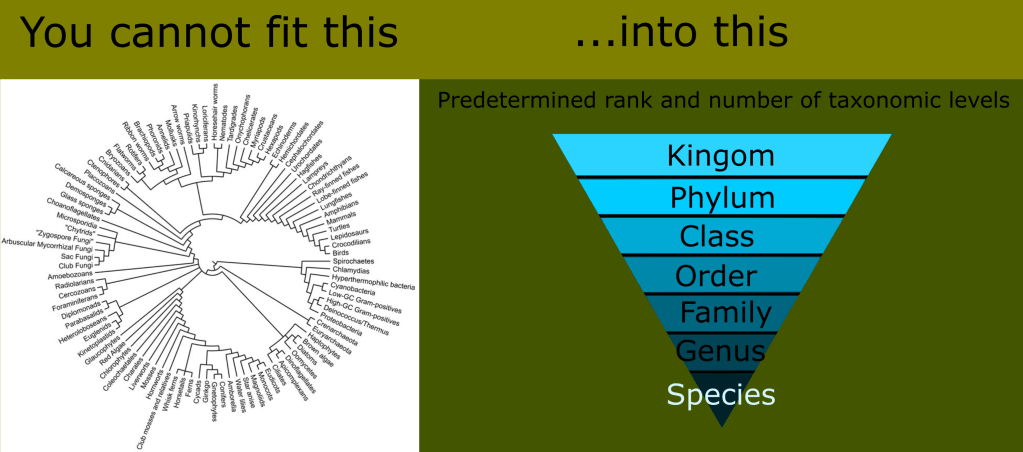

This was far from a handful of animals like the siren or platypus. These were entire ecosystems of unknown groups. The number of new classes needed would render the ranked Linnaean system far too unwieldy and awkward for any practical use. This is the reason for the use of monophyletic clades in lieu of ranks today.

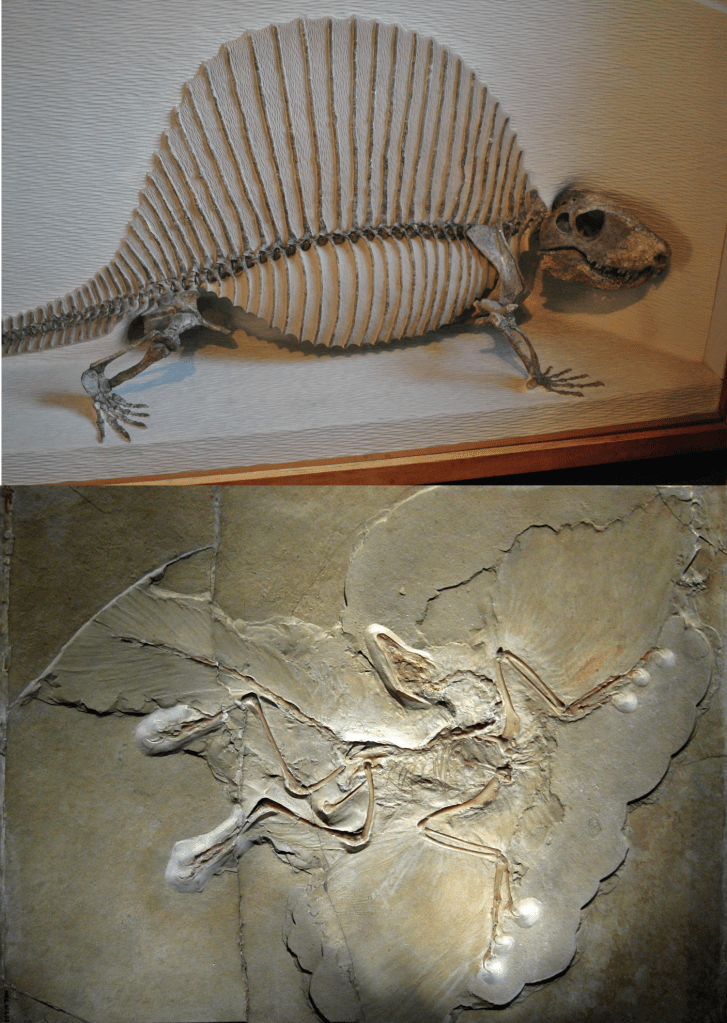

As the extinct species were examined and cataloged, it quickly became apparent that many of them had reptilian characteristics, but they were not anatomically modern reptiles. Stranger still, some of these “vaguely reptilian” creatures appeared in the lineage leading to mammals.

This meant that vaguely reptilian traits were basal to the amniotes. Even more intriguing was the discovery that the most famous of extinct animals, the dinosaurs, were not entirely cold blooded. What’s more, some of the more derived forms had…feathers. This meant that the ancestors of birds were also reptilian.

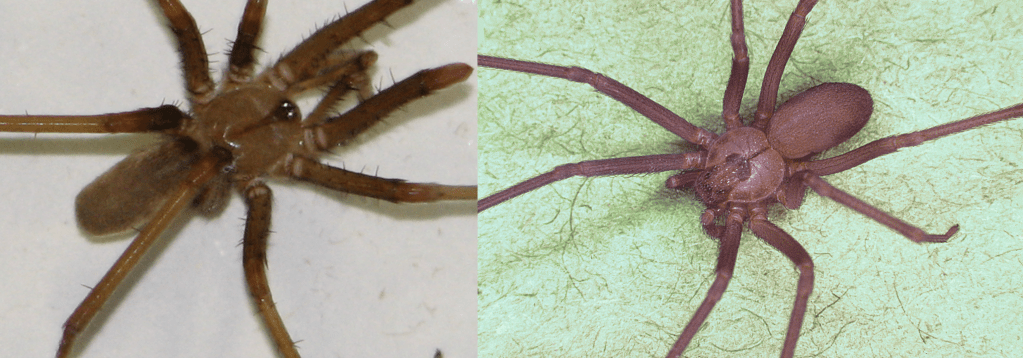

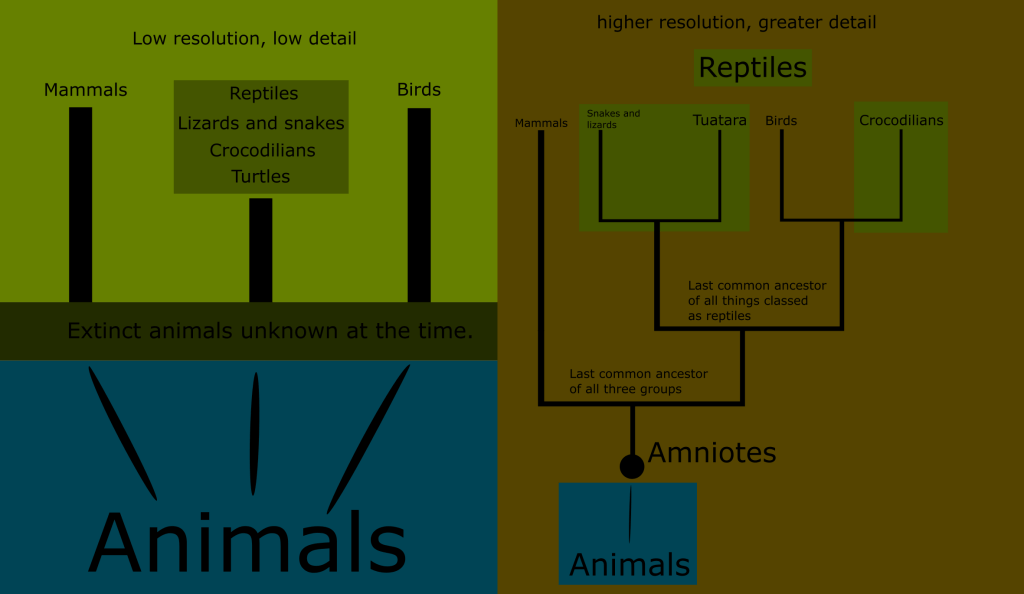

At this point, it was becoming apparent that “reptile” was a poorly defined category. It served as a “leftovers” pile for the amniotes after the mammals and birds were named. “Reptile” just meant “an amniote that isn’t a bird or mammal.”

Reptiles were defined not by what they are, so much as by what they are not. They were the default for amniotes that did not belong to any better defined group.

The realization that reptiles are actually several distinct lineages, but more closely related to each other than to mammals seems obvious in retrospect.

Snakes and lizards have so much in common and are so closely related that they pair together quite naturally, crocodilians share a number of characteristics with them and while they certainly are not lizards, they are obviously related.

But one group of reptiles as historically defined was always different. The testudines have a hardened carapace that forms a shell which encases most of their body. This is a trait entirely unique to them among the amniotes. Additionally, much of their skin lacks the scales typical of classical reptiles.

The reptiles were initially expanded to include the newly discovered dinosaurs and other non-dinosaur paleofauna such as pterosaurs and ichthyosaurs. The definition of reptile saw several revisions during the following decades, leading into the 20th century.

One thing was clear by the mid 19th century: mammals, reptiles and birds were all united by the amniote egg, thus revealing that amphibians were the outlier, representing a more basal state of terrestrial animals, with reptilian traits representing the next stage of development.

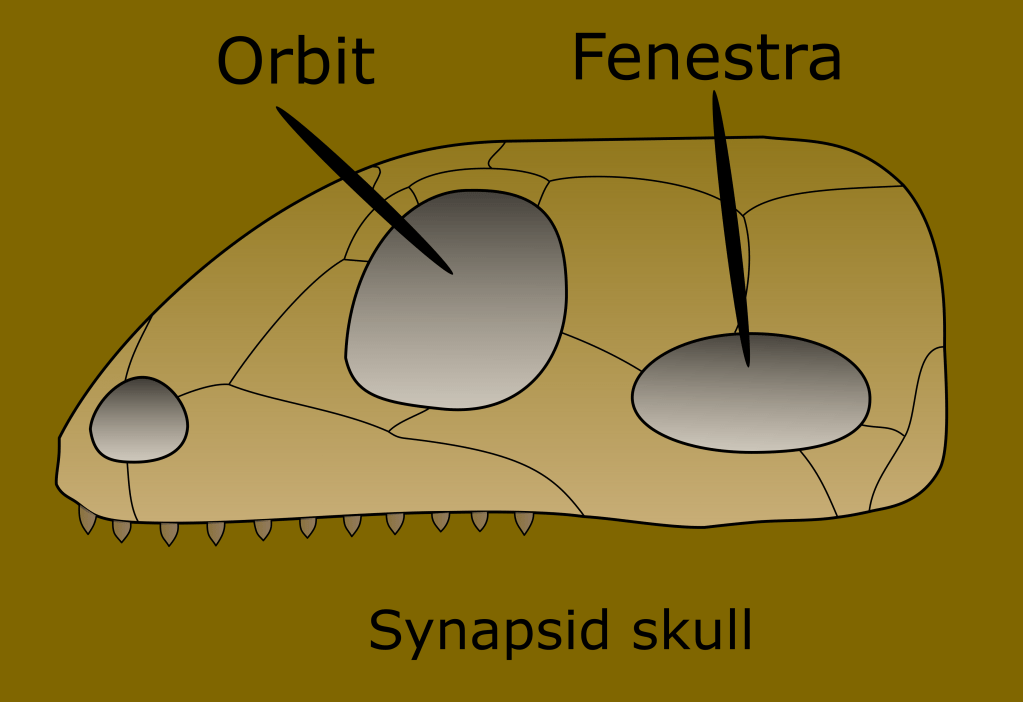

A clear distinction was found between the ancestors of mammals, and “reptilish things.” A synapomorphic trait that distinguishes the line leading to mammals from the rest of the known fossils at the time was the presence of a single temporal fenestra, which is an opening in the skull behind the ocular socket, the vestige of this are the temples in your skull.

By the way, a synapomorphy is a trait shared by descendant groups because it was present in a common ancestor, and thus defines the entire group (even if they lose the trait secondarily, like snakes did with legs, they are still tetrapods because their ancestors were.)

In 1863 paleontologist Thomas Huxley coined the terms Theropsids, or the “beast faced” animals and Sauropsids, the “lizard faced” animals to describe each side of the tree.

Although some of the early specimens on the mammal side of the tree were included with the Sauropsids in these early days, we were finally on the right track.

Around the turn of the 20th century, as more fossils were found our understanding of vertebrate evolution improved dramatically. By this time the resolution of the Therapsid-Sauropsid split was understood in much greater detail, and the name synapsid was now widely used to describe the mammal side of the fork.

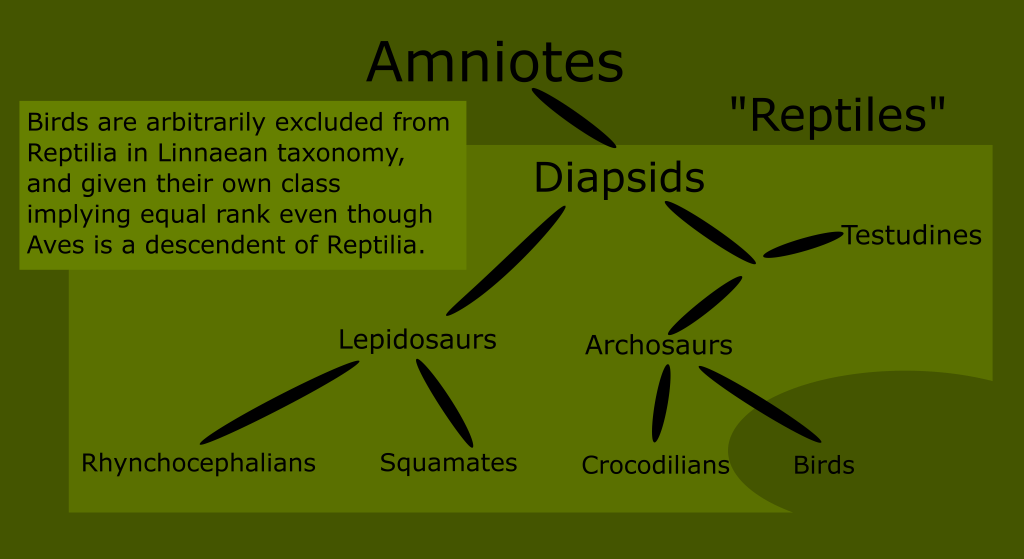

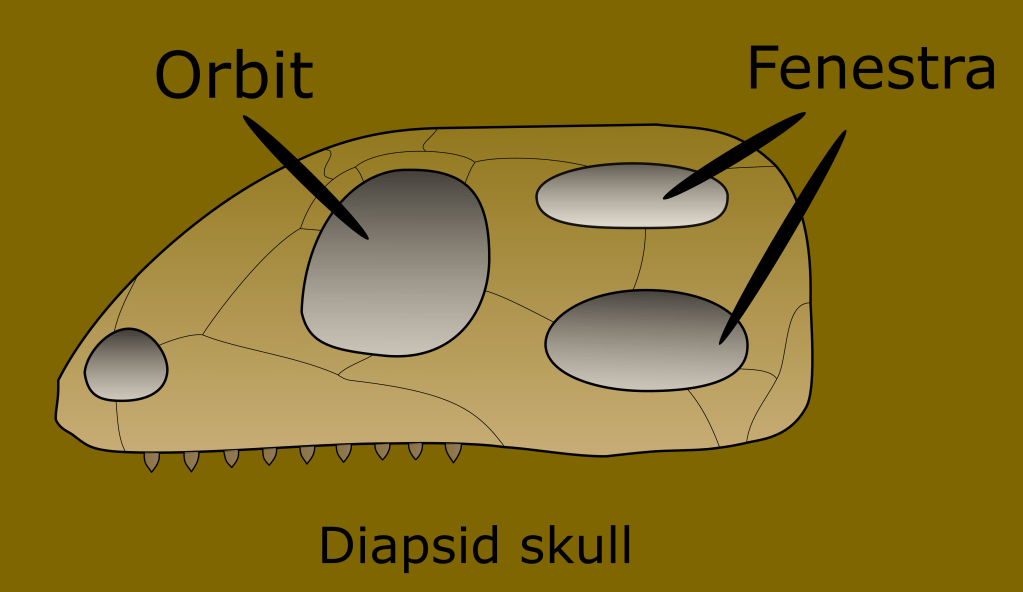

All extant Sauropsids are a part of a subgroup called the Diapsids. They are defined as having developed two temporal fenestra. This includes all birds, snakes, lizards, turtles and crocodilians.

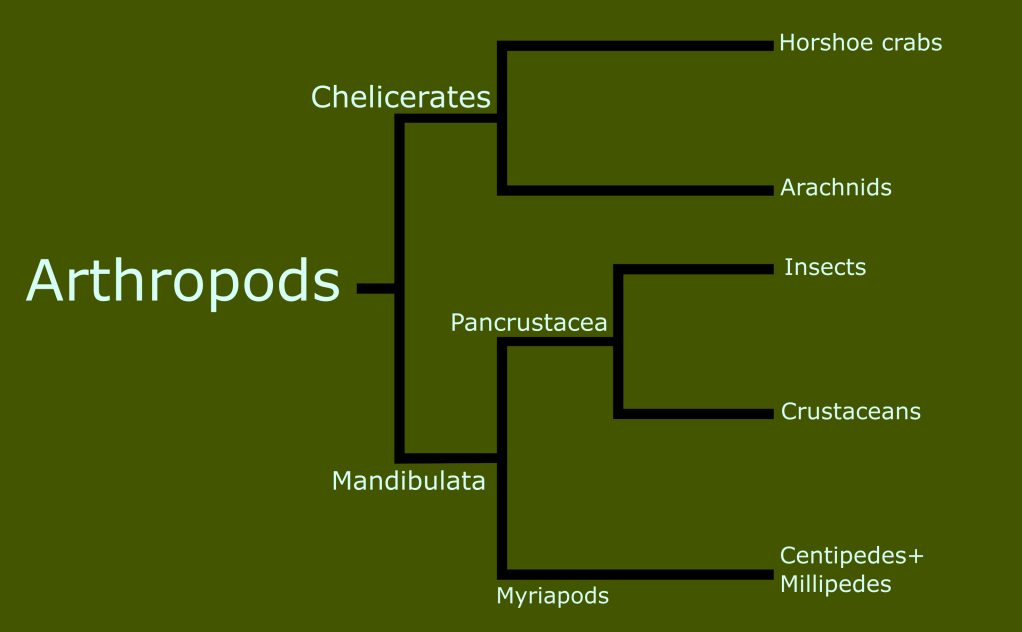

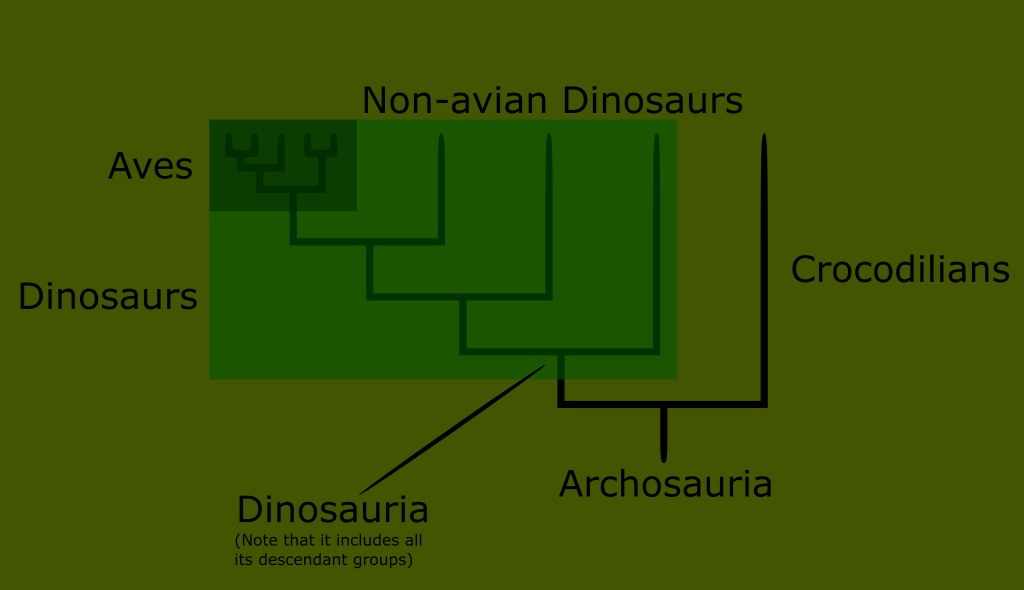

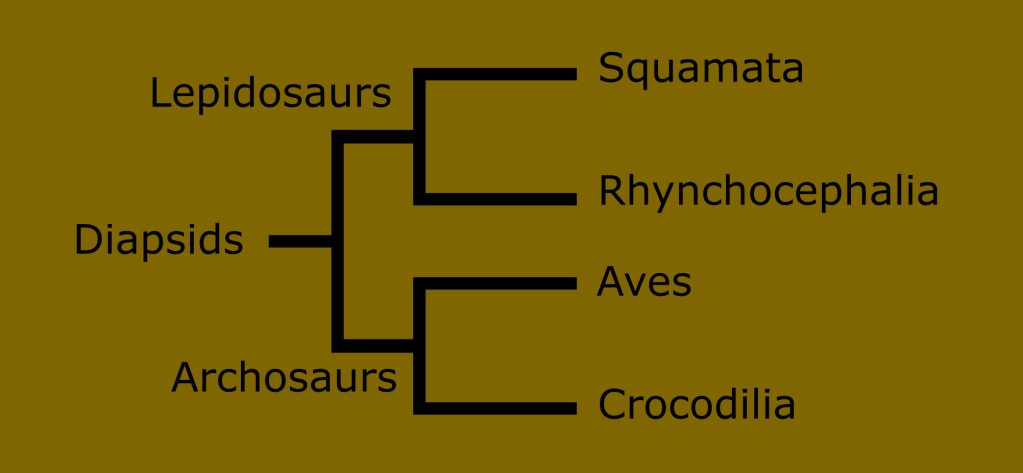

The diapsid tree has a fork early in its development separating the two broad groups of “reptile things” : the Lepidosaurs on one side, and the Archosaurs on the other.

The Lepidosauria consist of modern squamates, rhynchocephalians, and a few extinct groups such as (possibly) ichthyosaurs and the Keuhneosauridae.

The Archosaurs include the early branching Crocodilia, the world famous dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and of course the surviving subset of dinosaurs called birds.

It is likely that the Archosaur branch also includes the Pantestudine clade made up of turtles and stem turtles, including plesiosaurs.

Now that we have established a foundation for understanding the “reptile” side of the amniote tree, we can begin fleshing out the details a bit more in the next entry. For now, let’s recap a few points.

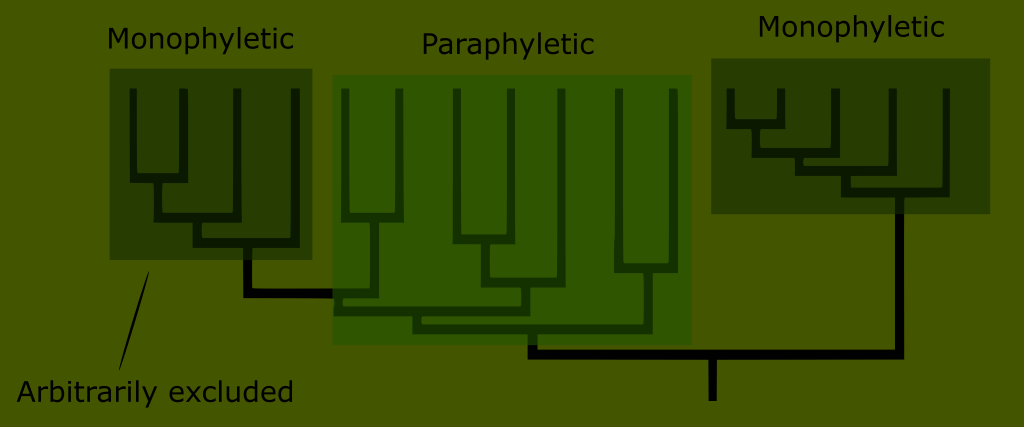

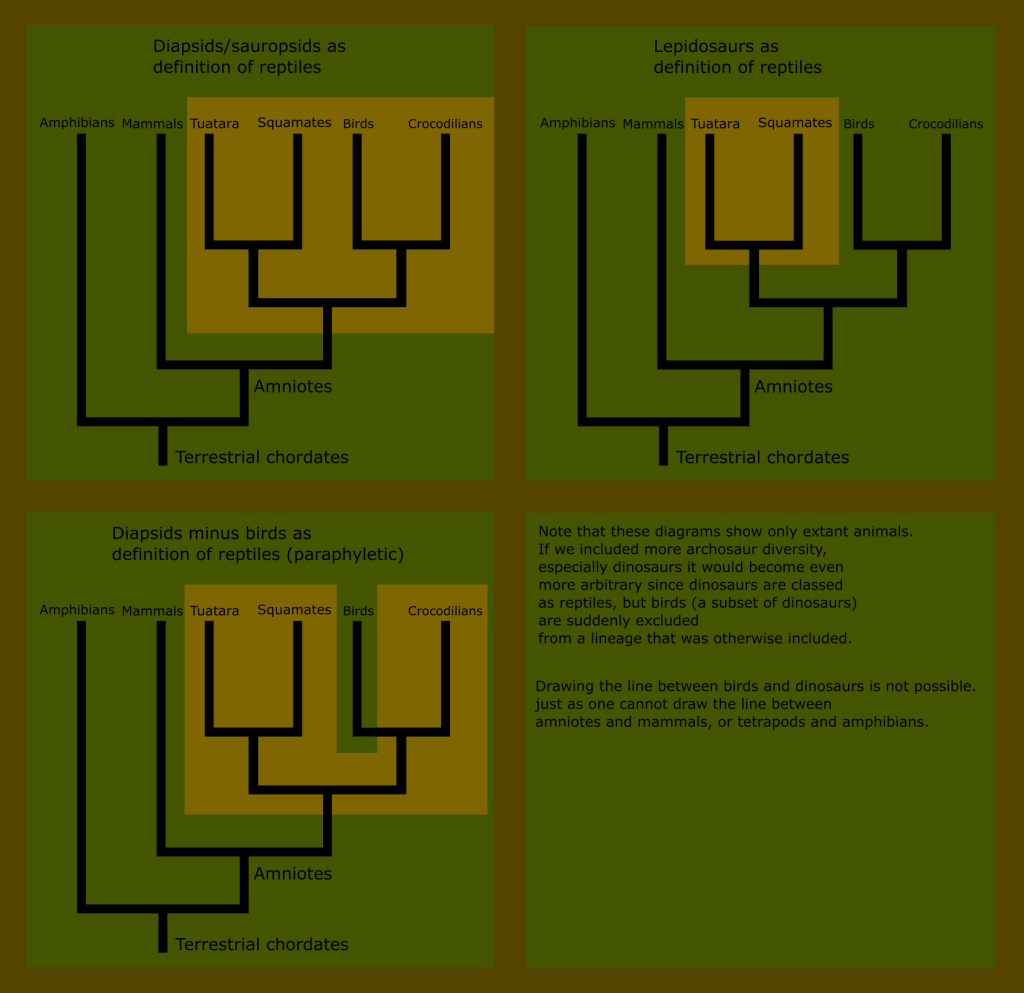

Remember that modern taxonomy seeks to create monophyletic groups, or a group that is defined by synapomorphies inherited from a common ancestor, and includes that ancestor and all its descendants.

For example, the mammary organs of mammals are synapomorphic, existing only in the mammal lineage and inherited from the last common ancestor of all mammals.

This is impossible with reptiles; because the “reptile” label describes a broader number of distinct groups than the other amniote classes.

You can see that no matter where we draw the line when trying to define what reptiles are, we either include birds, or exclude huge numbers of what have traditionally been known as reptiles.

Reptiles, as classically defined, are an invalid grouping, technically called a paraphyletic taxon because the group arbitrarily excludes some of its most recent descendants.

You may also notice that the phylogenetic position of the turtles was not shown on any of these graphics. This is because its exact placement is still being actively researched, and this group in particular has a variety of unique historical quirks that warrant a more complete treatment later on.

After we have fleshed out the Lepidosaur and archosaur trees, we will return to the reptile tree to bring it all together with the inclusion of the Pantestudines.

For now, I hope you enjoyed and that I was able to entertain you with a little history and taxonomy, and that you’ll join me next time.

Special thanks to Richard Wahlgren of the International Society for the History and Bibliography of Herpetology for compiling the majority of Linnaeus’ work related to herpetology.

When I set out to make this entry, I was very grateful that Mr Wahlgren had already done the legwork of searching and gathering the references from among Linnaeus’ voluminous works.

I have included a link to the paper published via ISHBH written by Mr Wahlgren below if you would like to read his overview of Linnaeus’ contributions to herpetology.