One of the very first creatures to capture my attention as a child were the large, black, velvety, spiders that built messy retreats under the eaves of my back porch. Something about these animals intrigued me, and made me want to know more.

I didn’t know anything about evolution at the time, but I did recognize certain traits about this particular species that reminded me of tarantulas, at least from what I had seen of them in books; though it would be years before I had the opportunity to see one in person. I couldn’t articulate exactly what it was that made this spider stand out from more typical spiders, but did recognize that it had features that most other araneomorphae did not.

It’s silky black hairs reminded me of a miniature version of the tarantula Pamphobeteus antinous. It’s broad and prominent coxae reminded me of pictures of large mygalomorphs viewed ventrally. It also has long pedipalps that almost look like a fifth pair of legs, another trait in common with mygalomorphs.

What stood out to me most was a unique attribute of its life cycle. Unlike other araneomorphae, and very much like more basal spiders, females continue to molt after reaching maturity, and can live for many years. This is the reason for one of its many regional names: the southern hibernating spider. So named because it lives year to year, rather than dying off each winter and hatching in spring as many other spiders do.

Even today, this particular species captivates me whenever I encounter it. So today we are going to look at this interesting animal, and try to understand its place in the world of spiders.

When I was first starting out in the invertebrate hobby, I often found that I had a desire to understand my favorite species in their greater context. For example, I knew that tarantulas were Mygalomorphs, but I didn’t know what this meant. I knew that it involved the possession of certain traits, but I didn’t understand why they have the traits they do, or where those features came from.

I found the subject of arthropod taxonomy understandably daunting, full of revisions, huge words that defy pronunciation, and a variety of subjects I would need to familiarize myself with before any of it would make sense. I suspect this is also the case for many people who enjoy the wonderful world of arthropods. Over the years, I have grown and done the ground work to open the door to understanding the evolution and classification of arthropods in a general sense.

For this reason, when I make a post about a particular species or group, I’ll try to include some taxonomic context to help these daunting subjects become a little more manageable, hopefully this will help you appreciate the nature of your favorite animals a little better as well.

Today We’ll take a quick look at spider taxonomy, which is a huge and complex web (pun intended of course) of relationships that are still being actively researched and refined. We don’t need to go very deep into the spider family tree, because our subject is very primitive compared to more derived species, it is found near the root of the araneomorphs.

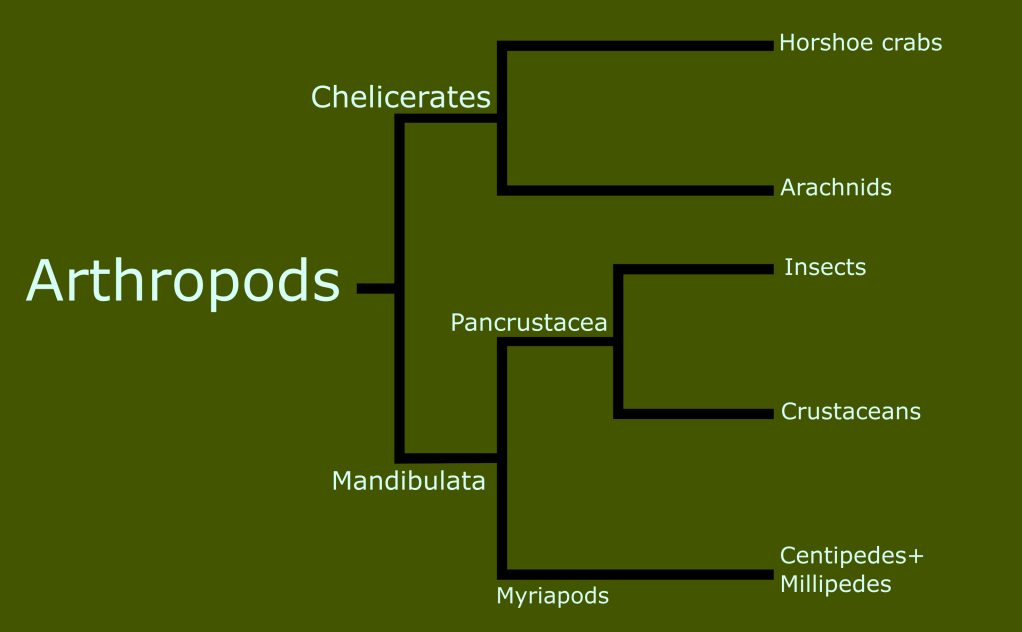

Remember that spiders are arachnids, which are a subset of a group called Chericerates, which are a subset of arthropods emerging during the mid-Cambrian about 500 million years ago.

As a group, chelicerates represent a more basal arthropod form than, for example, insects and myriapods. The exact relationships among arthropods is a complex web to untangle, since they are the single most diverse branch of animals there ever was. Molecular data is being used to establish some revisions, but that is a story for another time.

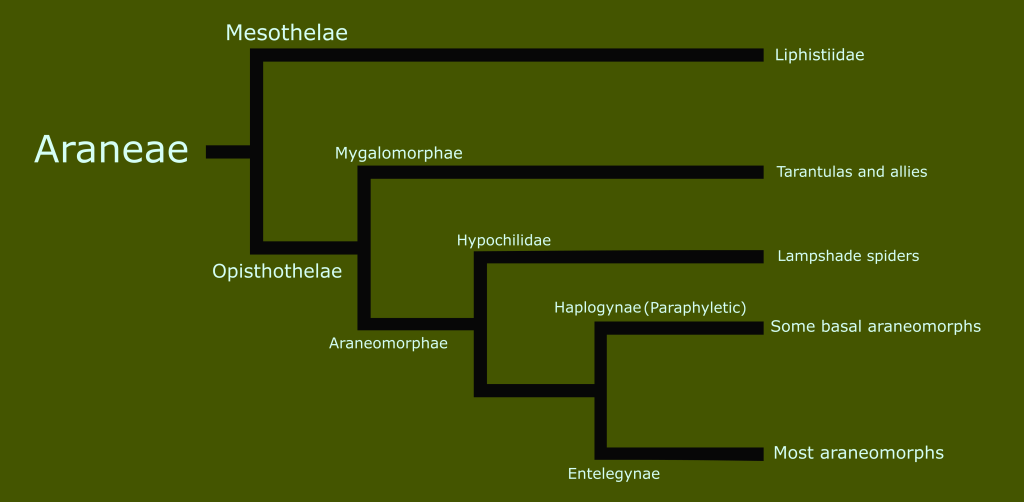

Spiders represent a subgrouping of arachnids that form the clade Araneae; or simply spiders. From here, the tree branches again into two groups representing the totality of what are considered to be true spiders; the opisthothelae, which includes virtually all extant spiders, and the mesothelae representing many extinct spiders, and only one extant family; the Liphistiidae.

The name Mesothelae means “middle nipple” named for their spinnerets being placed near the middle of the underside of the abdomen. Opisthothele means “behind or backward nipple” placing the spinnerets at the back of the abdomen as in most modern spiders.

Opisthothelae are further divided into two broad groups; the Mygalomorphae including tarantulas and trap door spiders, and the Araneomorphae which is all the rest.

Mygalomorph spiders retain a variety of basal spider features including the full set of 4 book lungs, and vertically operating chelicerae, but have lost some other features, most notably the (visibly) segmented abdomen present in most arachnids including basal spiders, and the complete loss of the anterior median pair of spinnerets.

Most Araneomorphs have lost one set of book lungs. While many retain the anterior pair, they now also feature a modified posterior pair as a trachea. Their fangs cross each other in a pinching motion, and they retain the anterior median spinnerets, or at least a vestige of it, more on this in a moment.

The next branch is where our subject can be seen on the horizon. Traditionally, araneomorph spiders have been split into two main groupings, the entelegynae, which possesses a hardened (or sclerotized) female epigyne and the more basal Haplogynae which lacks these more complex reproductive structures. A third clade, the Hypochilidae, are sister to all other araneomorphs and represent the most basal of all extant araneomorph spiders.

The vast majority of extant spiders are members of Entelegynae.

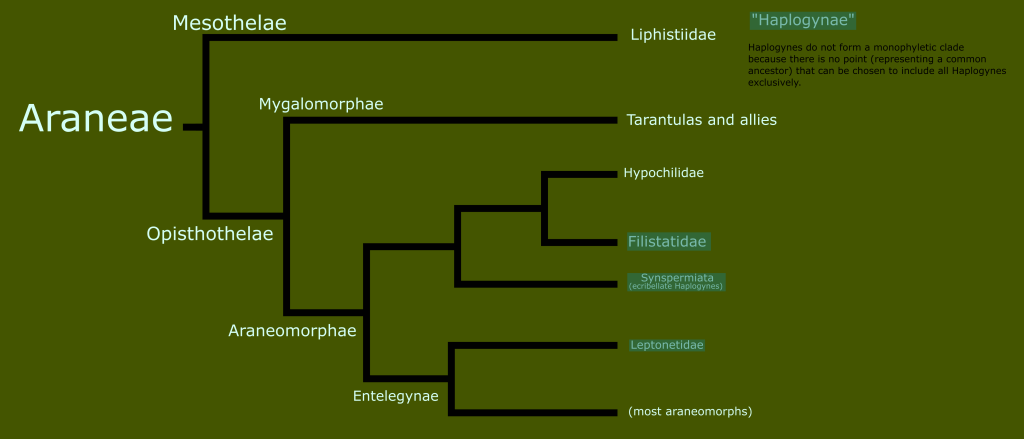

Recently, the grouping Haplogynae has been shown to be paraphyletic, meaning that it included a common ancestor for most (not all) Haplogyne spiders; that is to say that no common ancestor could be identified that included all (and only) Haplogyne spiders. This means that rather than two subdivisions of Araneomorphae, Haplogynae has been split into several groups to better represent the true relationships of extant spiders.

Molecular studies indicate that haplogynae did include a monophyletic clade, but that a few interesting outliers were lumped in with it, requiring reclassification. Most of the traditional Haplogynae were found to form a clade and are now referred to as Synspermiata, the ecribellate haplogynes. One family, the Leptonetidae was shown to likely be basal to the entelegynae, though this is tentative. More research will be needed to resolve these relationships in greater detail.

Another family, Filistatidae, was separated from the previous “Haplogynae” and placed as a sister group to Hypochilidae, the so called paleocribellate spiders. This means that Filistatids are among the oldest and most primative of araneomorph lineages. The Hypochilidae-Filistidae group diverged from the rest of the spiders during the mid to late Mesozoic era, 120-294 million years ago. They represent one of the earliest developments in araneomorph history.

The hypochilidae represent the most basal of extant araneomorph spiders. They possess the defining intersecting fangs, but still have four book lungs like mygalomorphs do.

Their sister group, the Filistatidae is what we are interested in today. Defining characteristics of Filistadidae include the retention of the cribellum, a structure derived from the anterior median spinnerets present in primitive spiders.

The cribellum is a silk spinning apparatus present in some araneomorphae, usually more basal clades. Spiders that retain this feature are referred to as cribellate spiders, those lacking it are said to be ecribellate. Most aranomorphs are ecribellate, but many still retain a visible vestige of this structure called a colulus.

The retention of the cribellum is one of the features that distinguishes the Filistatidae-Hypochilidae clade from Synspermiata, which are a collection of ecribellate Haplogynes.

The cribellum is made of one or more plates with small holes or perforations. Spiders that retain a cribellum also feature a comb-like row of hairs on the hind legs called a calamistrum. This is used to tease out the non-adhesive silk for the animal to use. The result is a mess of extremely fine silk strands. This unique type of spider silk is known as cribellate silk.

Because cribellate silk is not adhesive, the mechanism of prey capture relies on entanglement. The silk traps and entangles prey sort of like Velcro, the more it struggles, the more the tangled and wadded silk stretches and surrounds them.

Some examples of cribellate spiders of other taxons include the ogre faced deinopis, the industrious Agelenopis, a common feature in many backyards, the beautiful Eresus, and the fascinating and enigmatic Uloboridae, notable not only for being cribellate spiders that produce orbs, an advanced form of trapping generally seen in more derived spiders, but they are also entirely nonvenomous, having lost their venom glands at some point in their evolution.

With this understanding of the base of the spider family tree in mind, let’s return to our subject today.

Remember that Kukulcania hibernalis is a member of the family filistatidae, a clade of spiders near the base of the araneomorph tree. This spider represents a basal form of what is the beginning of modern spiders. Filistatids are an ancient lineage with their origins in the mid Jurassic, to early Cretaceous period.

Filistatidae and its sister clade Hypochilidae also do something unique with their cribellate silk; they fold it. Cribellate silk is already messy but this folding tends to create a very distinctive look for the silken structures of the group.

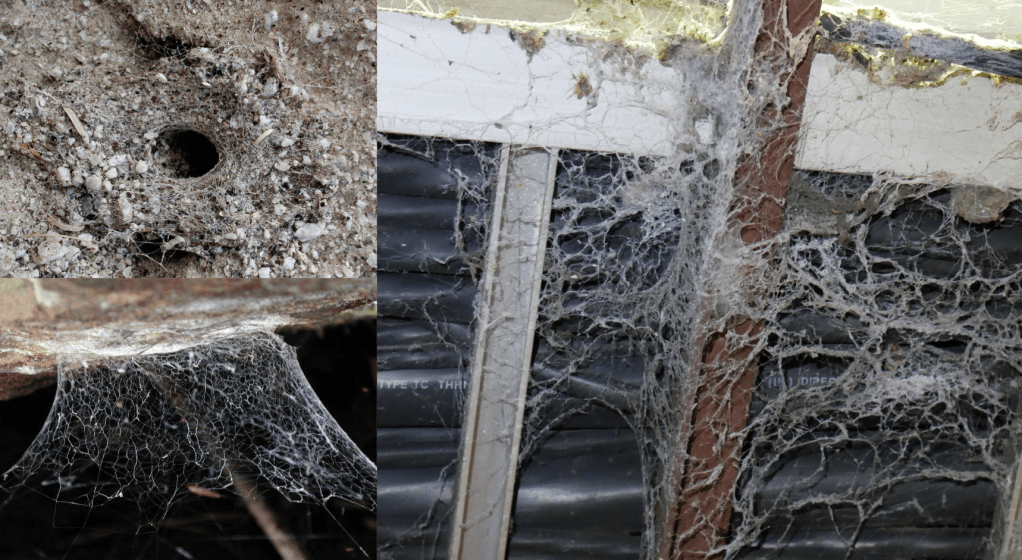

K. hibernalis is one of the most evolutionarily significant spider species you are likely to find in your yard. Common in dark, dry places like sheds, woodpiles, and underneath porch covers, this species is easily spotted from afar by its distinctively messy webbing.

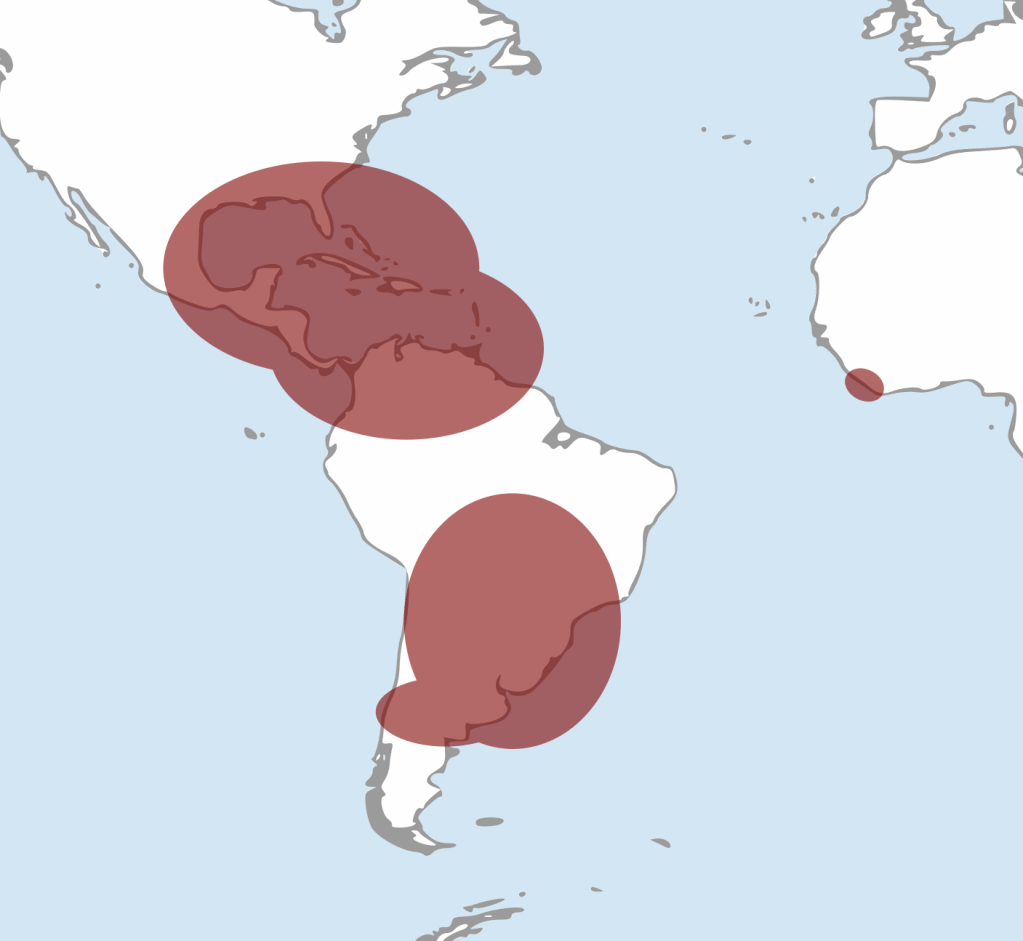

This species has an enormous distribution, being widely distributed throughout the southeastern United States, Central America, most of South America, and even one confirmed established population in West Africa.

They tend to prefer areas that are not often disturbed. I located most of the specimens featured in this video essay in an old pump room housing a colony several generations old, in undisturbed wire trays, and among the items on an old shelf. As a child I frequently found them under porches, in old sheds, and around plumbing.

You can see from the footage/images that they are capable of modifying their retreats depending on the opportunity. Sometimes they create neat holes, sometimes messy conglomerations. They can be oriented vertically, horizontally, or even entirely upside down. Most of the specimens I have encountered seem to display a preference for verticality.

I remember as a child I used to love sneaking out onto my back porch at night and see the large females just outside their silken retreat waiting for food or mates. These animals are easily startled, retreating at the first sign of danger. They are also easily teased out with a little movement.

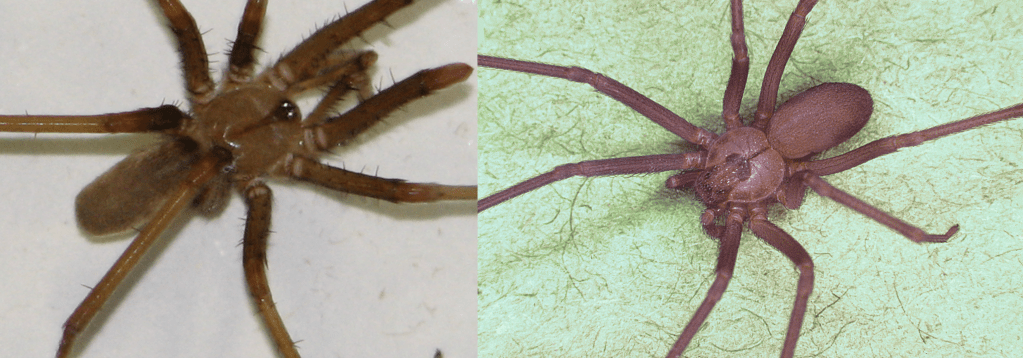

K. hibernalis also displays strong sexual dimorphism common to Filistatids. Upon maturing, males take on an entirely different color. Interestingly, the mature male of this species bears a remarkable resemblance to recluse spiders, Loxoceles species. This species is responsible for many false reports of introduced Loxoceles populations due to mistaken identity.

As an interesting side note, recluse spiders are part of Synspermiata, being members of the family Sicariidae. Like Filistatids, they were once grouped among the so-called “Haplogyne” spiders, but do not retain a cribellum, and only have six eyes.

Female K. hibernalis continue to molt regularly even after reaching maturity, a trait common to mygalomorphs, but rare among araneomorphae.

Another interesting feature of the Filistatidae is the temporary appearance of the posterior book lungs in early instars. An image of the vestigial posterior book lungs taken by scanning electron microscope can be seen on page 150 (figure 97, image B.) in this research paper.

These spiders seem to be remarkably tolerant of each other as well. Adults and juveniles can be found closely clustered together with little evidence of cannibalism. Even large females guarding egg sacs can be found inches away from other spiders.

Some research has been done that suggests that, at least as juveniles, this species could be considered borderline social. See the references below for links to a few papers examining this. Regardless of the degree of social behavior they exhibit, they do seem to be densely concentrated where the do occur, with populations occurring in clusters.

As you might expect, they are easy to keep in captivity, having a low metabolism and low dependence on moisture. A project I am working on is establishing a “colony” of sorts in captivity. I will update new footage and behavior when this project is complete.

One last interesting thing to look at is the mating behavior of this species. The mating ritual takes a bit of time, the male spends a while announcing his presence, drawing the female out without becoming dinner. It is also interesting to observe the resemblance to mygalomorph mating.

Overall, Kukulcania hibernalis is an interesting spider. Its early divergence makes it a classic choice for studies of phylogenics and comparative morphology. This relic of evolution and of my childhood will always catch my attention whenever I encounter it.

So the next time you find a big black spider in a messy web, before you reach for the bug spray, take another look, you may just be encountering something special.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoy content like this, please consider subscribing to our email list and follow us on YouTube and social media, and be sure to hit the notification bell to be alerted when new content is available.

youtube.com/watch?v=C6LqvevTU1o

Thank you, and see you next time.

Recommended resources:

Paper: “Growth and nest hole size preferences in immature Southern House spiders.” By James Carrel. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272088007_Growth_and_Nest_Hole_Size_Preferences_in_Immature_Southern_House_Spiders_Araneae_Filistatidae_Are_They_Constrained_Consumers

Paper: “Egg guarding and spiderling group-feeding in crevice weaver spiders” By Kathryn Macdonald and James Cokendolpher. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228366729_Egg_guarding_and_spiderling_group-feeding_in_crevice_weaver_spiders_Araneae_Filistatidae

Paper: “The crevice Weaver Spider Genus Kukulcania” by Martin Ramirez and Ivan L F Magalhaes. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331191512_The_Crevice_Weaver_Spider_Genus_Kukulcania_Araneae_Filistatidae